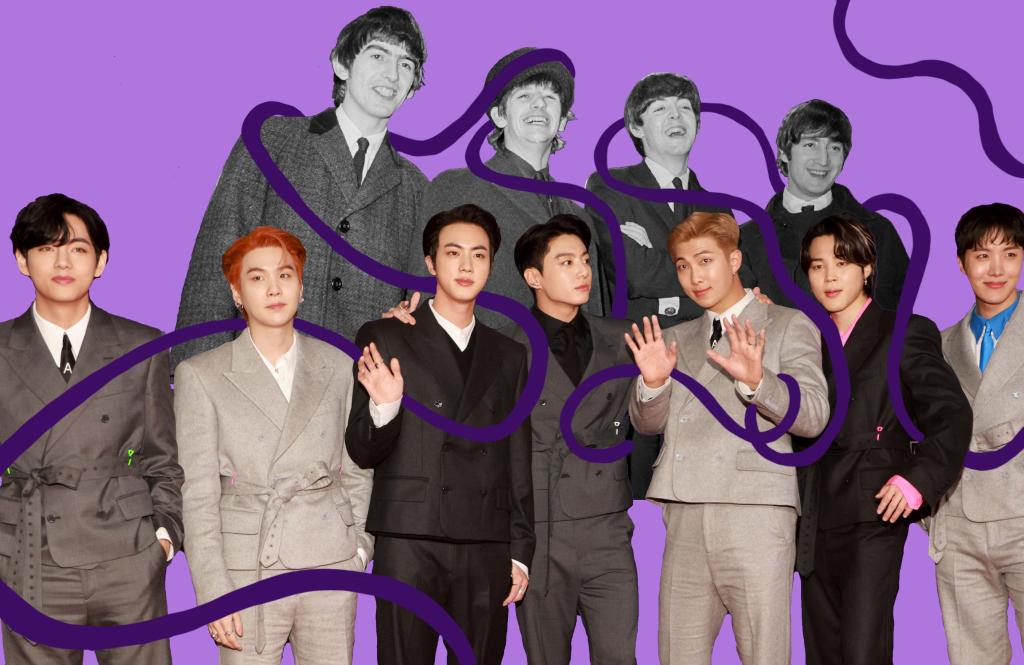

The Beatles and BTS - The power of Fandoms

What is a band without its fans? Ellie Field looks at two of the most powerful fandoms in music history, those of The Beatles and BTS, and reveals the surprising parallels between them.

The Beatles and BTS’s careers are around 40 years apart, but familiar patterns appear in the behaviour and treatment of both Beatlemania and ARMY (BTS’ fan base name). Their contribution to music has given both bands and individual members places in the Guinness book of records, with The Beatles having a total of 25 Guinness World Records and BTS 23. They’ve also both swept up a vast number of awards, BTS with a staggering 407, The Beatles with 12, bearing in mind a lot more award shows exist now compared to when The Beatles were active. In 2019, BTS became the first group since The Beatles to earn three No.1 albums on the “Billboard 200 Chart” in less than a year, a record held by The Beatles for 22 years.

What is Beatlemania?

The term Beatlemania was first used in the British press in 1963 to summarise the excitement and passion of its devoted fanbase that had developed due to their UK tour. Beatlemania expanded into the US after The Beatles infamous performance on the Ed Sullivan show in 1964 and the subsequent North American Tour. Despite The Beatles not disbanding until 1970 it is thought that Beatlemania tailed off when they no longer toured in 1966. It’s important to remember that without the internet and social media the only way to truly enjoy a full Beatles performance back then was to go to concerts.

Who are ARMY?

The term ARMY was founded in 2013 after BTS’s debut in South Korea. Naming a band's fan group is normal in South Korea, BTS were not the first to do it. You have for example Exo’s ‘Aeris’, Twice’s ‘Once’ and Black Pink’s ‘Blink’. ARMY is usually only ever referred to as ARMY, but it stands for Adorable Representative M.C for Youth. ARMY is still active today and is arguably the most global fan base in the world, with some form of subgroup representative in almost every country. BTS like The Beatles gained fans via the concerts they put on in South Korea and when they performed in the US the fandom grew even larger. However, their use of social media has certainly influenced the growth of the fanbase, this is proven by the 2-year gap of no tours by BTS during the COVID 19 pandemic where the fanbase continued to grow.

Bands interaction with fans

BTS and The Beatles both kept close contact with their fans, maybe not in the exact same ways but their willingness to be open with their fans and talk directly to them is what helped foster the loyalty of both groups. The Beatles employed Freda Kelly the President of the group's fan club as a secretary and frequently spoke to fans via her. One fan sent a request to Kelly asking if she could get Ringo Starr to use a pillowcase she sent and then return it to her address, Kelly got Ringo to agree and sent the pillowcase back to her. Kelly also helped with the production of The Beatles magazine, which became a useful resource for members of the band to share aspects of their daily life and answer questions from fans.

Since BTS’s inception, the band’s been prolific on social media, using twitter as a way to share their thoughts and daily activities. The use of Vlive was also crucial in creating a connection between the members of the band and their fans. Vlive is an app that allows band members to go live on-air and receive comments and hearts from fans, it has been around longer than Instagram live and other equivalents and is still used by a lot of Korean musicians.

Members would frequently go live and talk to fans, answer questions, eat food and sometimes even give a teaser of some music they were working on. The live streams even get views from fans outside of South Korea who can’t speak Korean, the idea that the fans are watching the band members live is enough to feel some sort of connection to them even though they may not know what they are saying. Social media in this case served as a digital version of Freda Kelly, a way to ask questions and feel connected to the band members despite not ever meeting them in person.

Another way both bands spoke to fans was via the music itself. BTS and The Beatles released songs specifically for their fanbases. From 1963 to 1969 The Beatles released Christmas albums sent out to their fan clubs, the albums contained covers of Christmas songs, skits and messages from the members thanking fans for their support, calling them "loyal Beatle people." George Harrison even wrote a song for a very dedicated subgroup called the ‘Apple Scruffs’ in 1970 after the band disbanded, the lyrics refer to the group religiously waiting outside Abbey Road studios. BTS have also released similar records for their fans, every year they release Season’s Greetings a specially filmed Christmas show that includes videos of the band talking, playing games, and answering fan’s questions as well as a book of festive photos of the band. BTS also include one song on each album that is specifically dedicated to the fans; songs that quickly become favourites. Many fans even go as far as to organise special events when those songs are performed on tour, organising everyone to hold up the same sign with the same message in unison.

Another parallel to draw is the interest over a band member’s personal taste. For example, George Harrison once let it be known that he likes Jellybeans which resulted in the band being pelted with Jellybeans on stage at their shows as well as receiving them in the post. An opposite but equally exaggerated reaction happened when the youngest member of BTS, Jungkook mentioned he liked a particular lemon flavoured kombucha drink, the following week the drink was sold out across the country, and he couldn’t buy it.

Reception

This enthusiasm and passion displayed by the fans of both The Beatles and BTS was and is frequently written about in the press as a crazied, frantic display of teen obsession. In 1964 Paul Johnson wrote an article for the New Statesman in which he said that Beatlemania was a modern incarnation of female hysteria and that the wild fans at The Beatles’ concerts were “the least fortunate of their generation, the dull, the idle, the failures”.

BTS fans have had a similar reception from the media, James Cordon was called out for referring to the fans as “15-year-old girls”, an almost accurate description that none-the-less implies their innate inferiority to more mature male fans. A downside of being part of a large group of fans with their own name like ARMY is that when members of that fan group behave badly the whole group gets painted with the same brush. This has been used frequently against ARMY who have members who run straight to Twitter to tweet awful things at anyone who says they don’t like the band. This has certainly tarnished the reputation of ARMY; the press writes about them now as if they are like a social media mafia you don’t want to mess with. In fact, the power of ARMY is frequently used for good. In June 2020 BTS donated $1 million to Black Lives Matter, within 24 hours ARMY matched the donation through a campaign on Twitter. On the members birthdays, fans make donations in the members names to a charity in their hometown instead of sending gifts.

It seems that whenever young women show a great interest and passion over a band/movie/brand etc it is often disregarded as a crazy obsession rendering all other subsequent fans open to ridicule. The reality is yes a lot of The Beatles and BTS fans are and were young teenage girls. However, by 1965 The Beatles fanbase also included folk and rock enthusiasts, the kind that had originally shunned the pop group. BTS fans likewise have developed throughout the years, ARMY has a variety of different aged members and subgroups. For example, one is called Bangtan Moms & Noonas (Noona is what a man would call an older woman in South Korea), their bio statement on twitter is “Never, ever, ever too old to fan girl…#DopeOldPeople”. BTS also has fans in some surprising celebrities, John Cena being one who has been warmly welcomed by the rest of ARMY.

Ultimately, we need to be looking at the fan groups of these two successful bands, not as the screaming crying girls in concerts who supposedly have no control over their emotions. But a group of powerful and passionate people who turn a small Liverpool band and a South Korean Group from a small unknown company into world-wide record-breaking sensations. Through comparing these two fandoms we can see how despite working in completely different decades and cultures the similarities in how they communicated to their fans.