De Morgan - the ‘Pre-Raphaelite Potter’

Victorian artist William De Morgan is celebrated for his wonderful lustre-decorated pottery and superb tiles. However did you know that ceramics were not his first – or even his last – career choice? Here are some fascinating insights into the creative career of William De Morgan. I hope that they might inspire you to never give up on your own creative journey.

Playing with fire

Painting, De Morgan’s initial artistic pursuit of choice, could possibly have led him into a quieter creative life, but he was technically inquisitive and stained glass-making and ceramics captivated him. Both activities involved extreme heat, carefully-controlled processes and a significant level of expertise.

Sunflower pattern tiles in red lustre, from early on in De Morgan’s career (left) and later (right). Lustre was a technically difficult method of decoration that De Morgan experimented with and succeeded in making one of his signature styles. Courtesy of a private collection.

It’s not surprising then that his family’s tenancy at a property in Chelsea came to an abrupt end when his kiln in the cellar caused a fire which burnt down the roof! However, “the landlord didn’t seem at all amiable” and in 1872 more appropriate premises were found nearby for the family home, where De Morgan’s studio and workshop were based for another ten years.

Following the death in 1871 of De Morgan’s father, Augustus, a mathematician and Professor of Philosophy at University College, his wife Sophia - educated and an early supporter of equal rights for women - continued to live with her son William’s experimental creativity.

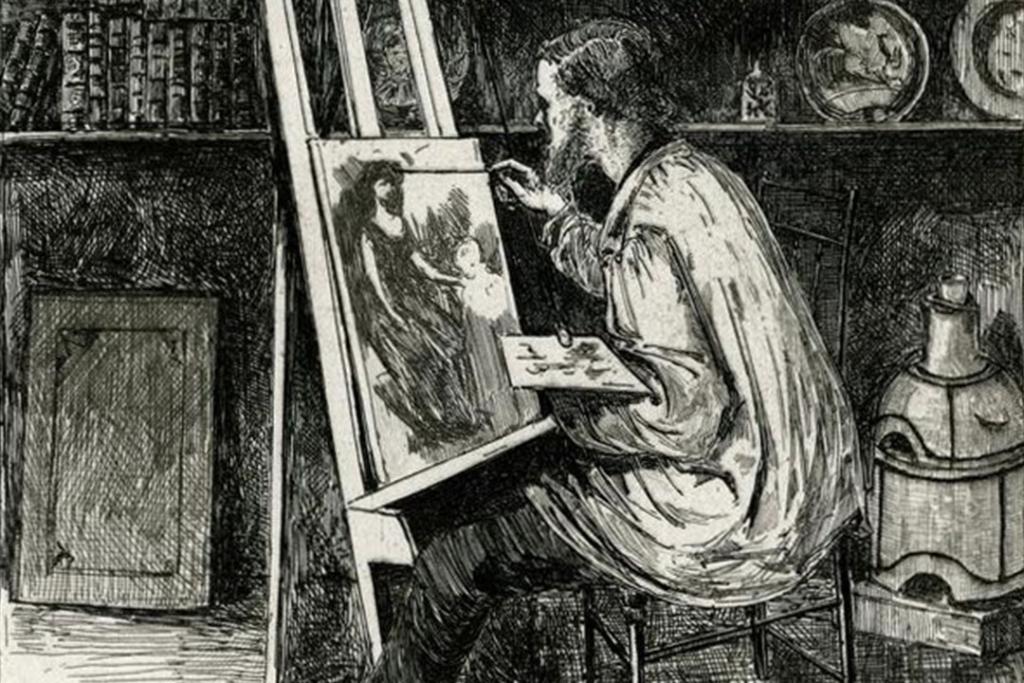

‘In the studio of a friend’ etching by Horatio Lucas of William De Morgan at work in 1871, probably not long before a serious fire. Painting at his easel, in the background are ceramics, many in the Japanese style, and other objects including a fashionable Japanese fan and leather-bound books. Bottom left is the artist's monogram and date. © British Museum, number 1872,1012.1784

It’s all about who you know

At the Royal Academy School of Arts, De Morgan’s network and his immersion in this cultural world flourished - before he dropped out early. In 1859, aged 20, he met key artistic personalities such as Simeon Solomon, and through Henry Holiday, De Morgan was shortly introduced to William Morris’s circle and the Pre-Raphaelite artists. Edward (‘Ned’) Burne-Jones and William Morris became two of De Morgan’s particularly close friends and collaborators.

These connections and De Morgan’s own design style have earned him the title ‘the Pre-Raphaelite Potter’, known for his experiments with ceramic decoration and making ‘art tiles’. Morris and De Morgan were design influencers and their style has remained popular in interior design ever since their heyday in Victorian Britain.

‘Poppy’ pattern tiles, designed by William Morris. De Morgan versions top and bottom, middle tile from Morris’s workshop. Courtesy of a private collection.

In 1863 De Morgan gave up painting - “I transferred myself to stained glass making” - and designed glass, tiles and painted furniture for the successful business of Morris & Co. Living in Chelsea in the artistic community, ‘alternative’ lifestyles and pet peacocks were commonplace - until peacocks were banned! But association with his artistic friends continued throughout his life and eventually, in his late forties, he married Evelyn Pickering, an accomplished artist whose own work was Pre-Raphaelite and Symbolist in style.

Tile-making revival

Tile-making in Victorian Britain enjoyed a phenomenal revival. Developments in ceramic technology were matched by the architectural ambition of Victorian designers and engineers and the desire for ‘artistic’ homes amongst the growing middle and wealthy classes. Inspired by medieval tile pavements, glorious tiling schemes of the Islamic world and the charm of Dutch and European tinglazed tiles, British designers and industrialists responded, establishing tiles as one of largest divisions of ceramic production.

De Morgan tile panel with an intricate interlocking pattern and colours inspired by tiles of the Middle East. © The Potteries Museum & Art Gallery

The new Houses of Parliament and the Great Exhibition of 1851 showcased the expertise of renowned makers, including the Minton factories in Staffordshire. Soon an international export market brought world-wide demand. Royal enthusiasm for tiling and mosaic schemes at Windsor, Osborne and Marlborough House embedded the popularity of ceramic decorations with British consumers.

De Morgan began to focus on tile-making around 1872, encouraged by William Morris. Many of the early designs and schemes were very much collaborative efforts. Owing to his social and artistic contacts commissions for prestigious clients were plentiful. Frederic (later Lord) Leighton commissioned him in 1877 to produce tiles in Islamic colours and style to complete the ‘Arab Hall’ at Leighton House, his home and studio, for which he had acquired spectacular tiles from the Middle East.

The ‘Arab Hall’, Leighton House where De Morgan was commissioned to complete a tiled interior of Turkish and Syrian tiles. He had been experimenting with the luxurious colours of ‘Persian’ ceramics in the 1870s and following this prestigious work, De Morgan added ‘Leighton Persian’ designs to his range of tiles available to customers. ©Leighton House/Bridgeman Art Library

A novel idea

De Morgan was encouraged by his father in his writing and later in life he returned to this for creativity and an income. From the early 1890s he did not enjoy good health, and he and Evelyn began to spend winters in Italy. This also led him to give up pottery-making and turn to writing popular novels. The first of these, Joseph Vance (1906), was an immediate success and more followed over the next eight years.

Courtesy of a private collection

Clearly based on the style of Charles Dickens, Joseph Vance has been described as “rambling but entertaining” and “an ill-written autobiography”. De Morgan's novels proved to be very popular with the public and probably much more affordable than his ceramics and tiles. Seemingly he made more money as a novelist than as a designer, so although his books are unfashionable while his design work is never out of style, both are inspired.