The evolution of Liverpool’s iconic waterfront

The ‘Three Graces’ on Liverpool’s waterfront are instantly recognisable as a symbol of the city. But did you know that these iconic buildings are relatively new additions in Liverpool’s long history? Assistant curator Jen Robertson takes us on a fascinating journey back in time, tracing the changing landscape of Liverpool’s world famous waterfront through paintings from the Maritime Museum's collection.

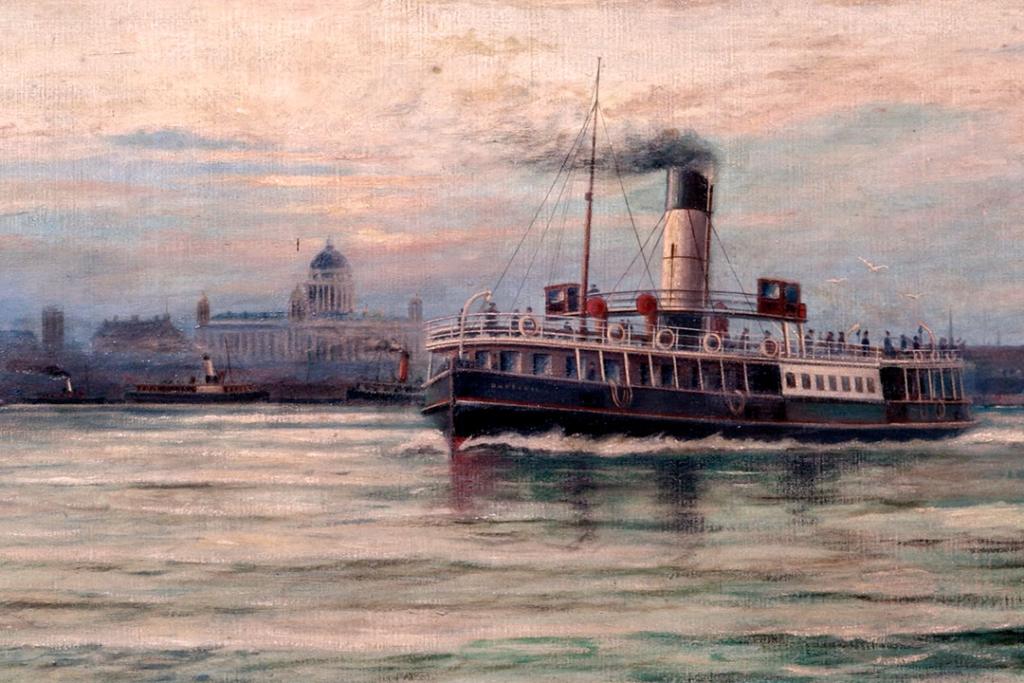

Detail from Pier Head, 1908, by Charles Cockerham (51.25.2)

If you enter Liverpool city centre by train you do so either underground or in a deep railway cutting, meaning you see very little of the city until you’ve left the railway station. By road you’ll see more, but we don’t have medieval walls or gateways to mark your entrance.

Arrive by ship though and you’ll feel like you’ve landed at the city’s front door. The waterfront is definitely our best side. As a port city we were designed to be seen from the river that has defined much of our sense of self. Liverpool’s rise, decline and subsequent resurgence link inevitably to our maritime industry and we have one of the world’s most well-known waterfronts.

Surprisingly, the map of Liverpool hasn’t changed that much through the years. Despite all the developments that have taken place, the original seven streets are still here, and the view of the city from the river remains recognisable even in scenes painted more than 200 years ago. What I love about these views of Liverpool is that you can see the city evolve over time, becoming slowly more and more familiar.

The earliest view

Liverpool in 1680 by an unknown artist (31.211.2)

The very earliest view we have might not spark much recognition, but there are a couple of landmarks that remain in one form or another that can be spotted in this view from 1680.

The church on the left is St Nicholas’ and a church of St Nicholas still stands on this site, though it isn’t the same structure. Also clearly visible is one of those original seven streets, Water Street, which we see in the centre leading up from the river into the town. The castle on the right is long gone now, its stones possibly reused in the earliest part of Liverpool’s docks. The tower in the distance is the Town Hall, also long gone but not geographically far from where the present day Town Hall is. Nearly 400 years ago some of the building blocks of the city we know were in place, but it’s not easy to recognise modern Liverpool in this painting.

The birth of the docks

A Prospect of Liverpool by an unknown artist, around 1725 (MMM.2001.8)

Moving forward into the 18th century and we have this rather unusual view of the city.

At first glance it’s perhaps even harder to recognise Liverpool in this painting than in its earlier counterpart. The castle has gone and St Nicholas’ church is only just visible in the far distance. However the key is right at the front on the right-hand side, where you can see (in what we think is its first representation in a painting) the world’s first enclosed wet dock. Liverpool’s Old Dock, built in 1715, was still brand new and a world changing innovation. Its prominence in the painting is a good representation of how important it was to the town’s commercial development.

A familiar view

View of Liverpool c1811 by Henry F James (55.411)

By the time we reach this early 19th century painting (circa 1811), the city has become rather more familiar.

The first landmark I look for in paintings of the Liverpool waterfront is the church of Our Lady and St Nicholas, long known as the Sailors’ Church and a key feature in many of the paintings of the waterfront. There’s been a chapel or church on this site since at least the 13th century. The oldest part of the present-day church is the steeple, which was rebuilt, following a disastrous collapse in 1810, in the Gothic style. The elegant lantern tracery is quite distinctive and makes the church easily recognisable in 19th and 20th century paintings. It’s said seafarers looked out for the Sailors’ Church as a landmark to show they had reached home. Indeed the previous spire, which collapsed in 1810, had been erected on the church tower in 1746 to enhance its usefulness as a navigational mark.

In this painting the church is just to the left of the centre and is the only one of several Liverpool churches we can identify in the painting still standing. The spires of St George, built 1734, and St Thomas, built 1750, can be seen to the right of St Nicholas’ and the dome of St Paul’s church, built 1769, is on St Nicholas’ far left. You can see St George's church from a different angle in this watercolour from the Walker Art Gallery.

Lord Street and St George's Church, Liverpool, 1828 by Robert Irving Barrow (WAG 1549). St George’s church spire is visible in a number of views of the waterfront.

There is another dome between St Nicholas’ and St Paul’s though and this is the other significant building we can still see today. It’s the dome of the current Liverpool Town Hall and was completed in 1802 as part of remodelling works to the building.

The city takes shape

View of Liverpool, 1873, by John W Carmichael (MMM.2001.174)

Moving on just over half a century and we can still see the domes of the Town Hall and St Paul’s and the spire of St Nicholas’. St Nicholas’ is still just to the left of centre in the painting but now we can see a new building on its right, Tower Buildings, built in 1846.

St Nicholas’ church (left) and Tower Buildings (centre with flag) c1898 (MCR/90/374 Archives Centre, Maritime Museum)

This is not the Tower Buildings we see on the waterfront today, nothing remains of it but the name, but it’s easy to spot in a number of late 19th century waterfront paintings from its shape and location beside the church, as shown in this photograph from our Archives Centre.

The most significant change we can see is St George's Pier Head public baths, opened in 1828 by the Corporation of Liverpool and roughly central in this painting, the long low white building easily recognisable. The watercolour below from the Walker Art Gallery has a closer view.

New Baths, George's Parade, Liverpool, 1828, by Robert Irving Barrow (WAG 1546)

The First Grace

Pier Head, 1908, by Charles Cockerham (51.25.2)

Jumping forward another few decades to 1908 and some significant changes have once again taken place.

The public baths are gone, demolished in 1906. Though you can’t tell from this painting, the 1846 Tower Buildings are gone too, along with St George’s Church which was demolished in 1897.

Most excitingly though, we finally have a sight here of the first of the Three Graces. The Port of Liverpool building, 1907, which is almost central to this composition. The Liver and Cunard buildings are still a few years off, but the iconic Pierhead is starting to take shape. St Nicholas’ remains a constant, though now pushed off to the far left of the painting behind the liner at the Landing Stage. Off to the right, behind the Mersey ferry, are the Albert Dock warehouses, opened in 1846, where the Maritime Museum is now based. There’s a suggestion of what might be the spire of St Thomas’ church rising behind the warehouse buildings. If so it’s one of the last times in the painting collection that we’ll see it, it was demolished only 3 years later in 1911.

Our iconic waterfront

Empress of Scotland in the Mersey, 1955 by David Gerard Watson (MMM.2004.12)

Now we jump forward to the mid-20th century to see a waterfront anyone who’s ever been to Liverpool (and many who haven’t) will instantly recognise. Here we see the iconic Three Graces completed. St Nicholas’ spire is visible between two of the Empress of Scotland’s funnels, with the 20th century Tower Buildings to its right, partly hidden behind the Liver Building, which was completed in 1911. The Cunard Building, the last of the Three Graces to be finished in 1916, is in place, and behind it and the Port of Liverpool building can be seen two more important Liverpool landmarks. We can see the white tower of the Mersey Tunnel building (a stunning Art Deco design from the 1930s) and the red sandstone tower of Liverpool’s Anglican Cathedral (a building whose construction spanned much of the 20th century, 1904-1978). To the far right you can see the Albert Dock warehouses.

What I like best about this beautiful painting is the fact you can see railings in the foreground, telling you the perspective is from a vessel in the Mersey. This is an artist who understood that the best view of Liverpool is, and always has been, the one you get from the deck of a ship.

21st century Liverpool

The Liverpool Cityscape, 2008 by Ben Johnson

© Gareth Jones

If you’d like to take one last jump forward, to the 21st century, then a trip to the Museum of Liverpool may be in order. In 2008 Ben Johnson painted an incredible modern image of Liverpool. The inspiration from those earlier waterfront artists is clear - painting the city the way it presents itself to the world, with the river as our doorstep. Something the painting shares with all the previous ones is the way it draws you in as you identify one landmark after another. You could happily lose hours examining it.

A changing cityscape

The Johnson painting and all those that came before it, captures a moment in time, moments that we can no longer see for ourselves. A reminder not to be complacent enough to think that our own view is the one that future generations will enjoy. Nor necessarily should it be. Without these changes we wouldn’t have the waterfront we do, that’s recognised by millions around the world. However, there are sights in these paintings of the beautiful buildings we’ve lost, and of buildings whose addition was not always well planned.

We talk of balancing the needs of heritage and community as though they were opposing things sometimes, but I’ve never seen them that way. It is the community’s heritage, some of it difficult, some of it proud, a history of how we lived, and how a city thrived, written in bricks and mortar.

What do you think the waterfront will look like in a few generations time? More importantly, what do you want it to look like?

We must not fall into the trap of thinking that heritage stands in the way of progress, any more than we must fall into the trap of attempting to freeze our view as a time capsule for the future. Heritage is at its best when it serves the interests of the community. I am lucky enough to work in a historic building which I believe does just that. Perhaps there weren’t many in the early 80s with the vision to see what the Albert Dock could become for the city, but it’s grown into one of our greatest assets.

After commuting to my office at the Liverpool waterfront for many years, I have been working from home since the start of the pandemic. During lockdown I did start to feel like one of those seafarers, longing for a sight of my home port. For anyone else longing to explore Liverpool but unable to visit just now, I hope these paintings help whet your appetite for when you can. I recommend taking a ferry to see Liverpool as it should be seen - from the river. It’s a wonderful view and one I hope I’ll never take for granted.