Ivory in our natural history collection

This article is the second in a series coordinated by National Museums Liverpool’s Ethics Group. The group is made up of colleagues from across the organisation who meet regularly to review specific ethical cases or concerns, and make recommendations for action.

World Museum contains around 1.5 million natural history specimens, they are a rich source of information about the natural world. Each specimen tells us a story. They provide evidence on where and when the organism was observed or collected. They provide us with a unique historical perspective on the distribution of bio- and geo-diversity, giving us a physical snapshot of a species at a particular point in time and space. Within these collections we have a number of ivory specimens which span two of our collection areas, vertebrate zoology and geology.

Ivory is not just from elephants

When people talk of ivory it immediately conjures up for me images of large elephant tusks, but it also occurs as the tusks and teeth of other animals. In 2019 the government requested information in order to better understand the issues relating to the non-elephant ivory trade. It was carried out with a view to increase the restrictions on these materials, in line with elephant ivory, in order to protect these endangered animals.

Potential protection of ivory-bearing species covered by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), includes hippopotamus, killer whale, sperm whale, narwhal, walrus, common warthog, desert warthog and also the extinct mammoth.

Why do we keep ivory in the collection?

Within a museum, how we view natural history specimens is different to how we view works of art. These items are not collected to be gazed at as objects of beauty and craftmanship, they inform us about our natural world in which we live. These are scientific specimens; they give us insight into how species have evolved and adapted over time. They inform us on the age, size and even diet of the animals and how our modern counterparts have arisen from extinct ancestors.

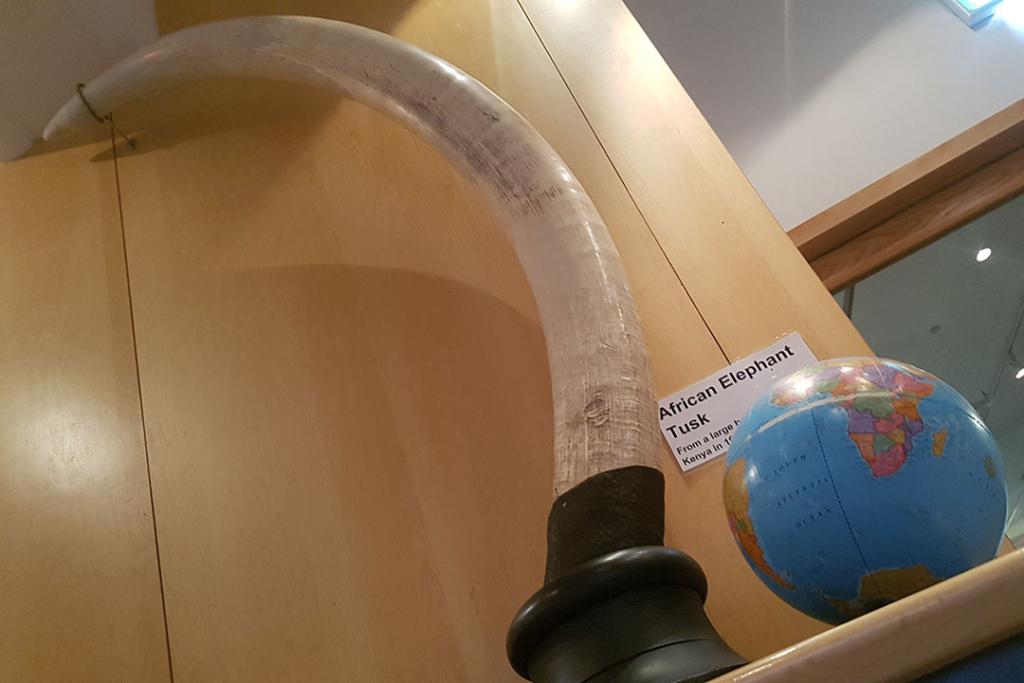

The power of an object to tell a story about the injustices and cruelty of the past and present is immense. An object can convey so much more than an image; to hold, to touch, to realise the majesty of these magnificent animals is mind-blowing. To see a child understand the size and scale of these animals just by seeing a specimen is what it is about. For example, in our Clore Natural History Centre we have two large African elephant (Loxodonta africana) tusks either side of the seating stage in the school room. Thousands of children across the region get to interact with these each year and really understand the sheer scale of the animals.

As well as the obvious, telling us about what these animals are like and stories such as conservation, big game hunting and illegal trading, they have hidden histories these specimens can be reflected in our colonial past which are stories we need to tell and explore.

Liverpool’s whaling industry

The sheer size of the sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus) jaw on display at the Museum of Liverpool must make people wonder how on earth we could kill these amazing creatures. With what appear to be huge dimensions of 2.45 x 1.4 x 0.4 m and a weight of 49kg this was a small sperm whale, probably around 10-12.25m long (32.81-40.19 feet), but I still find it quite a staggering sight.

Sperm whales are the largest of the toothed whales; males are typically 15.24-16.76m (50-55ft) and females 10.36-11.58m (34-38ft) long. The sperm whale has 36-52 cone-shaped teeth in its lower jaw which fit into sockets in the upper jaw. The teeth, which are hollow for the first half of their length, weigh up to 1kg (2.2lb) and can be 20cm long and 8cm wide. The teeth were used by whalers who crafted them into practical and decorative pieces with inked engravings know as scrimshaws.

The whaling industry led to the near extinction of large whales, including sperm whales, until bans on whale oil use were initiated in 1972 and tightened further in 1985. Liverpool used to have a thriving whaling industry operating in Queens Dock at the end of the 18th century. In 1764 it had just three boats, but at its peak in 1788 it operated 21 whale ships which would sail to the Arctic to hunt whales. In 1788 the Liverpool fleet brought back 76 whales between them. The number of boats gradually began to decline with just one boat sailing from the port in 1823. This was an important economy for the wealth of the city with up to 1,000 men per year from Liverpool sailing to the Arctic in the peak. Whaling also supported a whole industry within the city, from ship building to corset making.

Between 1814-1822, 10,889 whales were killed from Greenland and the Davis Straits by British boats. This is at a time when the industry was declining in Liverpool but increasing in other parts of the country. People are familiar with Liverpool’s colonial wealth from the transatlantic slave trade and the cotton trade, but many are unaware of our past connections to whaling. Like many of our other colonial actions of the day it is not one to be proud of.

Revealing the impact of human activity

Some specimens indicate the grim truth behind their collection, with a label attached to the tooth of a sperm whale saying "this whale produced 65 barrels (8 imperial tons) of oil of 900 pounds value. It measured 68ft". This must have been a huge male specimen as males are typically 15.24-16.76m (50-55ft) and females 10.36-11.58m (34-38ft). The tooth was also accompanied by the tooth of a calf. As a society we need to heed how we caused the near extinction of this species in the past to try to stop the same things happening again.

Specimens are our physical evidence that a species was in a certain location at a certain date, we use them to investigate how an ecosystem has changed over time. We need them to understand diversity and the impact of climate change and pollution, they are vital for us to understand these global problems. Our natural history collections hold specimens dating back more than 200 years and these are crucial as they cover a time when humans have been altering the environment through industrialisation, pollution and increased consumption of natural resources. This impact of human activity has become so marked that some scientists have called this time period the Anthropocene to chart the impact humans have had on the history of our planet.

Learning from the past

The reality is an animal has at some point in time died to find its way into a natural history collection. At National Museums Liverpool we follow ethical and conservation guidelines and would not expect anything to have been unlawfully or unethically collected to be made part of our natural history collections today. The ivory specimens within the collections date mainly from around the colonial eras.

I suppose our question of why we keep ivory in natural history collections all boils down to why do we keep dead things? Once you understand that hopefully you agree that our collections are an important resource for now and importantly for continued use in 100 years. They will help our future scientist understand our impacts on the world and for us now to be able to tell stories of our past, to help us learn and to shape our future.

I am hoping that this series of articles will enable us to reflect on the callous ivory trade, but also it has opened the opportunity to listen to the voices questioning the ethical aspects of continuing to display ivory in museums. Do you think we should continue to display these items?