Knots landing

Greek legend says that King Midas tied a cart to a post with an intricate knot. An oracle foretold that whoever untied the knot would become King of Asia.

Years passed and the knot remained untied until 333 BC when Alexander the Great tried to unravel it. His solution was to cut the knot in half with his sword.

The prophesy was fulfilled when he went on to conquer Persia. I suspect the knots mentioned below would have been easier for Alexander to untie.

Seafarers in the days of sail literally had to know the ropes – but knots were equally important. Ships could have 25 or more sails which harnessed the power of the wind with the aid of ropes and knots forming the rigging.

Large varieties of knots evolved over the centuries as vessels became more and more sophisticated. The knots had to be able to withstand the stresses and strains created by all types of weather and wind strengths.

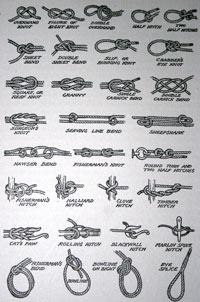

The names of knots evoke the romantic era of sailing ships. Some, such as slip and reef knots, are still familiar and in common use. Less well-known are cat’s paw, crabber’s eye, Turk’s head, sheepshank, halliard hitch, carrick bend and granny knots.

Reef and bowline knots were probably the most important methods of tying ropes while the others were useful in certain applications.

Today there is great interest in knots, how they are created and their history. Basic knots can be learnt by practice which makes it easier to interpret diagrams and pictures illustrating more complex creations.

Learning how to tie knots, which requires patience and dexterity, reveals patterns in their structures and tying methods.

Complex knots can be changed and rearranged usually by pulling on rope ends in certain ways – this is called spilling or capsizing. For example, the carrick bend is usually tied in one form then capsized to make it stronger.

The invention of wire rope in the 1830s brought a strong competitor to traditional hemp rope. Wire ropes had clips and shackles rather than knots.

A spin-off from the mariner’s knowledge of rigging was decorative rope work. A number of examples are on display in Merseyside Maritime Museum’s Life at Sea gallery.

A hand-worked pochette is a particularly fine example dating from 1930. It was made from cotton twine by retired Captain Eckford when he was a passenger on a voyage.

A new Maritime Tale by Stephen Guy appears every Saturday in the Liverpool Echo. A paperback – Mersey Maritime Tales (£3.99) – is available from the museum, newsagents, bookshops or from the Mersey Shop website (£1 p&p UK).