The last King's Regiment Chindit on Merseyside

On 15 August we commemorate the anniversary of VJ Day or Victory over Japan Day. In the second article marking this we focus on the memories of a King's Regiment Chindit who was there.

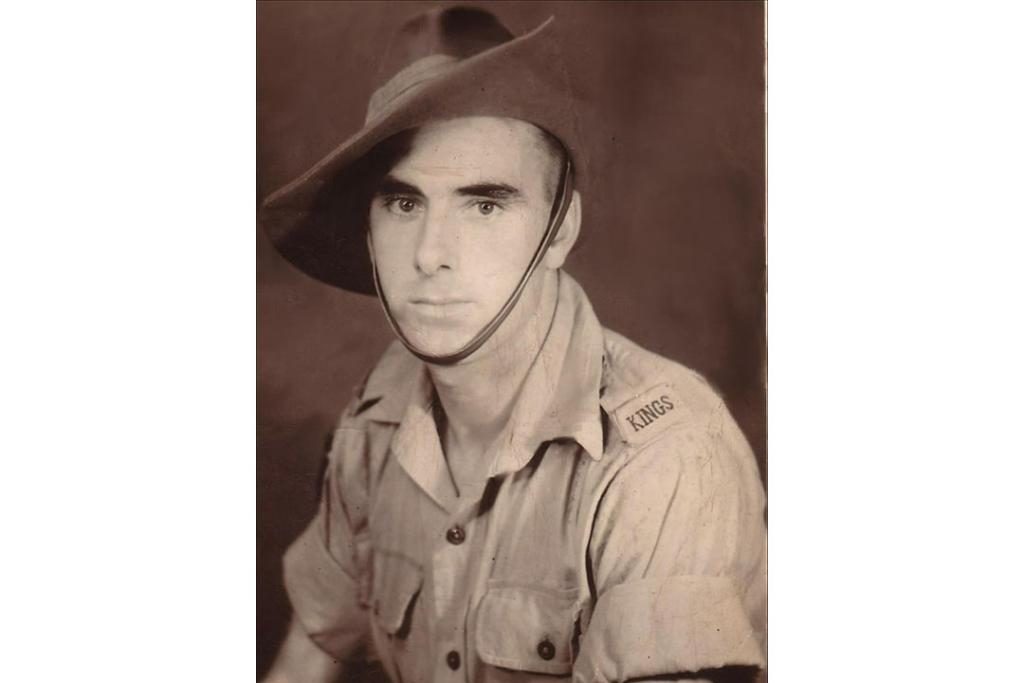

In my last post I wrote about the part played by the King’s Regiment 13th and 1st Battalions from journal extracts we hold in the archive. I would now like to focus on Philip Hayden who was the last remaining King’s Regiment Chindit living in Merseyside; he sadly passed away in January 2016 at the age of 96. The photograph above shows him around the time of the Second World War.

My colleague Karen O’Rourke interviewed Philip back in 2014 and he left a lasting impression on her:

"Philip had an amazing recollection of that time. He told me about some of the horrors that happened on the mission, having to bury some of his comrades, and how horrific jungle warfare was, but he also has an incredible sense of humour and had me laughing at stories of training in India before the expedition and talking to locals in Burma. He was a true gentleman and I am honoured to have met him."

Philip at the Wave and Weeping Window poppy sculpture in front of St George’s Hall, 2016, courtesy of Elaine Overend, Liverpool City Branch, The Royal British Legion.

Philip had joined the Territorial Army in Liverpool and served at the King’s Regiment barracks in Townsend Lane until he was called up in 1939 at the age of 19. Philip was then stationed in India and spent several months training in the Bombay jungle before moving to Assam to be part of the multi-national Chindit Special Force.

Operation 'Thursday' - March 1944: British, West African and Gurkha soldiers waiting at an airfield in India before the second Chindit Operation. They flew in by towed gliders where landing could be dangerous, up to 40 men were killed or injured. © IWM EA 20832

Philip painted such a clear picture of his life as a Chindit that I think he should tell it in his own words, these are just some of the extracts from his oral history interview:

Draft into the Chindits and the onward mission

"...when I first went abroad, there was only 55 of us, from the King’s…they wanted a quick draft, we had to get out there fast and... I volunteered, stupid bugger I was, and I was the only one, they said ‘get your kit packed, you’re going abroad’... we didn’t know where we were going actually, they just said that it was a very important draft.

...it wasn’t India where we went in from, it was Assam, a place called Laligat and all the planes were lined up and the gliders were lined up behind on a tow rope, some planes took two gliders up at once and some took one up, but the ones that had the two gliders on, most of them come down in the rivers over there in Burma, the Chindwin or the Irrawaddy you know, and they had to swim back to shore... The first time that I saw the gliders? I didn’t like it, no way, oh I said surely we’re not going to get in that? Because you went in one door like that and you went to the left like that and you just had a small floor, a wooden floor and two benches one on each side and in between on the floor they had all your ammunition, arms and guns and everything, but if you’d have gone to the other side you’d have finished up back down where you came from, cause it was only canvas!’"

Operation 'Thursday' - March 1944: American transport aircraft towing gliders toward Burma. The first wave of Chindits would be landed by gliders and would then prepare the airstrips for aircraft to land. © IWM SE 7946

Landing in the Burmese jungle

"...it must have been one o’clock in the morning, and you can imagine that in the jungle, one o’clock in the morning, pitch black, it was worse, and as they were coming in, we were one of the first off, we had to clear everything away from the other gliders behind us coming in and you couldn’t hear nothing, just, it was like a very strong wind blowing you know and then you knew they were there then, all the way in, on down you know, you just had to lay flat, but we had to go out and find one, we actually saw him coming in and he must have been over-shooting the runaway you know, and they tried to go up again like that you know, well you couldn’t have done that, there was no engine, no engine like you know, and it just went up and seemed to stop and then fall back down again you know, and we got, they were all killed in there, there were 24 in there we got out, all dead, some of them were still alive but the medical officer had to come around and give them extra morphine you know to see them off ‘cause they were in that much of a state, we buried them when we got daylight, we buried them in the one grave."

An aerial view of ‘Broadway’ blockade surrounded by dense jungle © IWM

Operation 'Thursday' - March 1944: The completed landing strip at the airstrip code-named 'Broadway'. An American Sentinel L5 liaison aircraft is on the runway. © IWM SE 7937

The Japanese Army attack on the blockade

"...they landed opposite us, you had the airstrip that we’d done there, we were on this side with the blockade you know and they were on the other side, and they come, it must have been about 10 o’clock at night, and they had two elephants, and they had heavy guns, one on each elephant, 8 millimetres they were and they opened a couple of rounds up and sent them over, but they were flying over us you know and as soon as our artillery boys got the distance you know, ‘cause you could see it in the dark as soon as the lights come on, and we fired a couple of rounds back over and we never heard them anymore"

Camp patrol

"...you’d stay in the camp…you’d form a section and you’d go out on patrol, , walking around, especially in the daylight…Twice a day, morning and night, first thing in the morning 5 o’clock you were up what they called a ‘standing to’..."

Protection within a ‘foxhole’

"Well we were digging, we had our own fox-hole you know, wouldn’t be deep you know, be up to your waist, that was far as you get and you were always in pairs, you never on your own, you had a mate, you had one end of the fox-hole, he’d be there and you’d be at the other end you know, but through the night time they used to shout to us you know, you could hear them, and they always called us ‘Johnny’, ‘Hey Johnny, come and see what I’ve got for you Johnny’ things like that you know and they were, what they were trying to do then was find out where the machine guns were, ‘cause they only had single rifles, and we had the Bren gun on each, each side and this is what they were after to find out where, where the machine guns were."

Supplies dropped from American Dakota planes

Two-day rations for the Chindits contained biscuits, dates, cheese, sugar, salt, chocolate, matches, tea, powdered milk and cigarettes. The packs were dropped by parachute and contained the equivalent of 10 days-worth of items.

"...called ‘K rations, oh I remember never felt anything like it in all your life and we used to get an issue of them, fifteen boxes, they were about that long and that wide you know just fits into your pack on your back you know, by the time they were in there, you were carrying about sixty pounds actually, and a lot of the boys were dying, they were getting malaria…they had a tin of meat in and they were marked breakfast, dinner and supper you know but they had these rounds tins of meat in there and they were all actually solid with grease you know, they were horrible..."

Jungle creepy crawlies and monsoons

"Oh leeches, well they weren’t so bad, they... got through the boot laces ‘cause they were that thin just like maggots and that’s how they got in onto your feet, and then your legs but when they started get itchy, you’d got your trousers up and they’d be about that big... with the blood that they’d sucked out of your legs, the only way you could get them off would be if you had a bit of salt, pour a bit of salt on you know and they used to wriggle up and just fall off, or you light a cigarette you know, put the... end of the cigarette on them they’d fall off but they were like fat sausages when you got them off.

I used to urinate in my boots... this used to keep the centipedes out and the scorpions out, if you didn’t do that and you put your foot in the next morning you were a hospital case, scorpions and centipedes, snakes, the other bad thing we had there when we were there was the monsoons... the rain was absolutely heavy, really heavy and it was pitch black... thunder and lightning, and then about three quarters of an hour after it would go all quiet and then the sun would come out, it was amazing and you were walking around and everybody was steaming..."

Meeting a well-known glider pilot of the US 1st Air Commando

"[The Americans] ...were all big, broad jobs you know they were…and they were all on cigars, big cigars(!) we’d never seen a cigar, and one of them was called, his real name, he was a film star actually, his name was Jackie Coogan and he was married actually to Betty Grable, she had the twenty million dollar legs you know..."

Cravings for food

"...you’d have some cheese or sweets you know but the thing I used to long for, I’d really yearn for was a tomato or an onion, especially an onion you know, and I could smell the onions you know just thinking about them!, especially fried onions, but there was nothing like that there"

Moving out and the journey back to India

"...we had to get shot of this blockade that we had... we were 150 miles behind [enemy] lines as a soldier and the [Japanese] started getting pushed back onto us... and they were getting short of food and everything, Mandalay…had a single railway line and a single road running from there to a place called Mogaung they were blowing the railway, the engineers were but we had to give them covering fire and they were blowing the railway line, and the supplies coming down to the Japanese lines were getting slower and less and less and less, and they were all dying... we had to get out and the march was terrible, we had to climb up hills you know and the monsoons had not being going that long, and the mules were with us, great, great little horses, they had a load on each side and a load on the top and they had to climb these hills, and the legs would be sinking right down in the mud and then they couldn’t get up, we had to get our hands underneath the belly you know and undo all the the shackles that were holding them along, take the weights off them, that’s how we could get their legs out of the mud then, anyway, we got over the top, the other side and went down into a valley there called the Mogaung Valley and that had only just been captured by one of our officer’s then [Brigadier Mike Calvert]…we had to go another 40 miles up the line to a place called Mishima and how we got up there it was on a flat railway waggon and they had a jeep in the front and a jeep in the back, take, took the wheels off and they were the same gauge and that’s how we got up to Mishima, and it was a big airfield, and there was a fella ‘Vinegar Joe’ [U.S. Lt-General Joseph “Vinegar Joe” Stilwell], he was in charge of a full battalion of American trained Chinese, we were there for a couple of days and then the old Dakotas come in then you know, ah doors open onto the Dakota you know and back into India"

Fatigue and illness

Philip and the Chindits endured awful conditions in the jungle including tropical diseases, malnutrition and fatigue.

"...if they give you a little bit of time to yourself say an hour or maybe two hours you’d get your blanket down and your, and your ground sheet down, and you tried have a bit of sleep you know and it’s surprising how you fell asleep you know, you just went off but you could go for a full day without sleep again, you were, it was driven into you, you know what I mean, you had to put up with it, you had to get used to it you know."

"I used to stand on guard, rifle and bayonet…and I just flaked out you know, finished up in a military hospital and I was there for just over a week, that’s where I got cured, well they said you’re going, you’re going back to your unit you know, I said well I don’t feel fit enough to go back to my unit you know, ‘cause I felt really weak, that’s the way sandfly fever used to get yer but they said well you’ll be alright once you get back and you start eating again you’ll be ok but, after that, after a while I got malaria"

"I’d lost a lot of weight, I was about eight stone, normally I used to touch the scales at about eleven and a half stone…I got malaria and I got…relapses after one dose altogether and I had that for three weeks after I come home when the war finished."

Chindits at rest in their jungle bivouac. © IWM IND 2291

Family and faith

'...couldn’t contact them at all [Philip’s family], couldn’t write or anything, and they couldn’t write to me, and that’s what they used to send, a little square called a airgraph stating that I was alright, I couldn’t send any messages or if you wrote a letter to keep it, they’d tear it up, wouldn’t send any mail home or nothing"

"I never stopped saying my prayers when I was in there... it wasn’t as if I was never afraid but it was the way I was brought up actually, I’ve never forgotten my prayers at all, never, you know mentioning my own family... but I was frightened, a fella saying he wasn’t frightened, he’s a liar, I don’t believe that... my prayers got me through because I know it wasn’t only me that was saying me prayers, it was me mother and father you know, always, I was always thinking about them, the family you know."

The last Chindit

Philip was honoured by The Lord Mayor of Liverpool in 2014 for being the last Chindit left in Liverpool. Family and friends continue to think of Philip with great fondness and are proud of his Chindit legacy which they hope he will be remembered for by future generations.

"I was with the 1st Battalion the King’s Chindits, I was a Kingo, I’m always a Chindit at the same time... If I am the last one, it’s a very nice thing to know"

VJ Day links