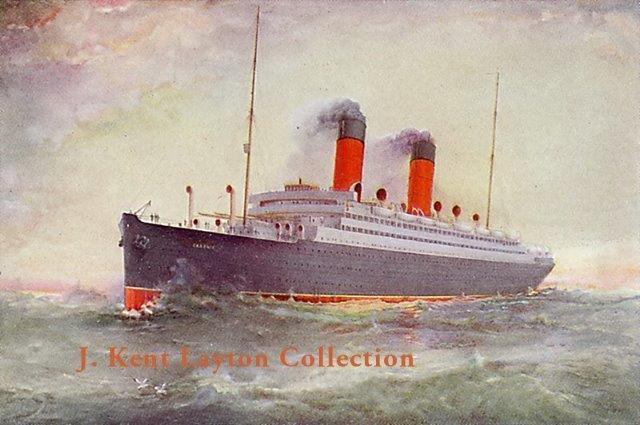

Lusitania: an engineering triumph

Contrary to popular opinion, the decision in favor of turbines on the Lusitania and Mauretania had nothing to do with the success of the Carmania over her sister Caronia, pictured here. (J. Kent Layton Collection) This blog post is the second in a series written by maritime historian and author J Kent Layton, the author of ‘Lusitania: an illustrated biography’, to accompany the exhibition Lusitania: life, loss, legacy at the Maritime Museum.

In order to propel the Lusitania at an unprecedented 25 knots, it was clear that something unique was going to be required in the design of her powerplant. Initially, the Cunard Company was feeling conservative, and wanted to use reciprocating engines—they were tried, tested, and reliable. Yet calculations showed that 60,000 or more horsepower would be needed to achieve 25 knots; in order to get this much horsepower out of reciprocating engines, a quartet of five-cylinder engines would be required in each of the new vessels. Along with the steam-generating boilers, this sort of powerplant would have taken up so much space that there would have been precious little room for passengers and cargo. There was another possibility, however: the marine steam turbine. Introduced by engineer Charles Parsons in 1897, this engine showed great potential in developing the required horsepower, but in a much more compact form than reciprocating engines. However, there was also risk: turbines had never before been implemented on this scale. Faced with no practical options, the decision was announced in June 1904: the new liners would employ turbines.

This view shows much of the Lusitania's revolutionary equipment

and machinery in the workshops prior to installation aboard. (J. Kent Layton Collection)

A quartet of turbines would be installed for ahead thrust on the Lusitania, two high-pressure and two low-pressure, driving four propellers. For astern thrust, another pair of low-pressure turbines was installed. A similar installation was employed on the Mauretania. In order to test the operation of turbine engines, and secondary systems which aided in their operation, Cunard asked John Brown to take the liner Carmania, then under construction, and convert her to operate on turbines. Her older sister Caronia would make do with the traditional reciprocating engines. This brings me to a fine opportunity to 'burst the bubble' of an age-old maritime myth: as the Carmania did not enter service until December 1905, and the decision to install turbines in the Lusitania and Mauretania was made a year and a half before, the Carmania's turbines and performance in no way contributed to the decision to adopt turbine technology on the Lusitania and her sister. Instead, valuable data was gathered in the operation of turbines on an ocean liner, and in the best way of arranging them and their secondary systems.

In addition to turbines, the Lusitania also utilised more technology, or technology on a grander scale, than any ship which had come before her. An elaborate system of electric lighting, electric lifts, telephone switchboards to communicate between rooms, and a state-of-the-art Marconi system of wireless telegraphy... all of this meant that the Lusitania was truly on the 'cutting edge', that she was truly an engineering triumph."