‘Matisse has all the worst art-school tricks’ – Sickert’s trash talk

As well as being a renowned impressionist artist, Walter Sickert was also an art critic and wrote many scathing reviews of his contemporaries. Dr William Rough takes us through some of these scorching critiques and how this affected his reputation in the art world.

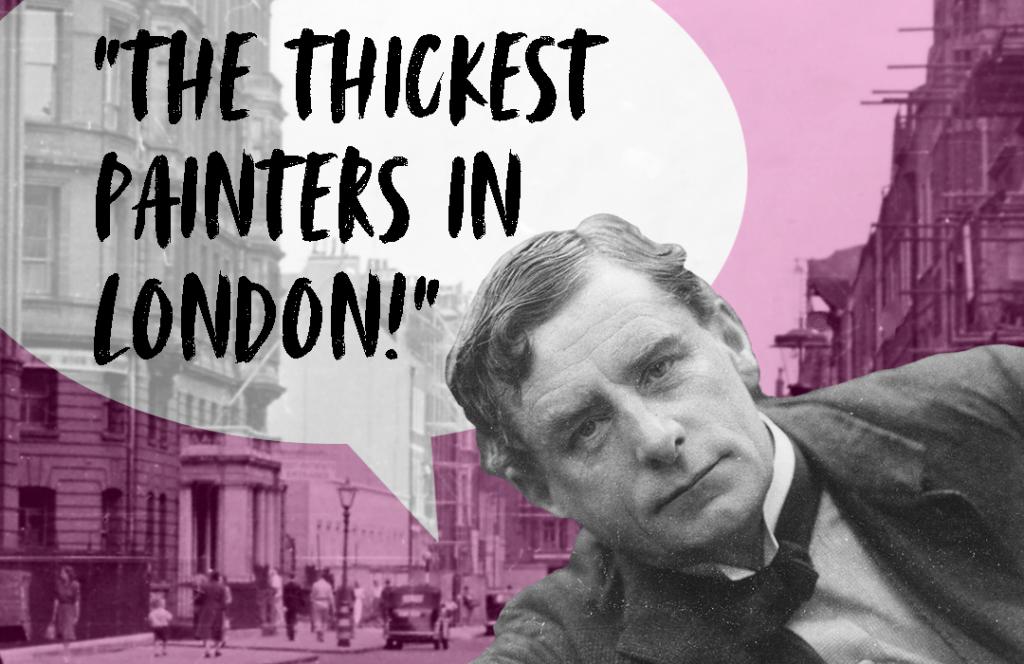

Walter Sickert by George Charles Beresford, vintage copy print, 1911 © National Portrait Gallery, London

One of the strangest modern developments is the painting critic.

Walter Sickert, 1897

Roger Fry’s ‘Manet and the Post-Impressionists’ exhibition was the first major exhibition in Britain to introduce audiences to contemporary artists such as Picasso, Matisse, Van Gogh, Gauguin and Cézanne. In his role as occasional painting critic and ambassador of Impressionism, Sickert’s thoughts on the exhibition were hotly anticipated. A knowledgeable and humorous commentator on art, his review was a masterclass in showmanship and calculated humility. Sickert took no prisoners, whether they be artists, ill-informed critics, or zealous curators.

A particular fly in Sickert’s ointment was Fry’s elevation of the recently deceased Cézanne. Sickert was aware of Cézanne’s Impressionist associations, so promotion of the artist above his contemporaries provoked him. He was particularly irritated by the ‘Cézanne-boom’ of the 1910s, where ‘...no self-respecting undergraduate is without his “crumpler", a “crumpler” being, I am told, the beginning of a picture or a reproduction of a picture by Cézanne.'

The Murder, Paul Cézanne, 1867 - 1870 (on display in room 10 at the Walker Art Gallery)

This unease saw Sickert consider Cézanne’s work, and its reverence, with the eye of a cynic. This ‘faux fauve,’ he wrote,

was fated, as his passion was immense, to be immensely neglected, immensely misunderstood, and now, I think, immensely overrated.

Whilst Cézanne devotees attracted his frustration, Sickert reserved his sharpest criticism for two new names: ‘Matisse has all the worst art-school tricks’, he wrote, whilst he simply dismissed Picasso’s cubist portrait of the art dealer Clovis Sagot as ‘nonsense’. His opinion certainly hadn’t softened a few years later, when he wrote:

Picasso’s tedious invention of the puzzle-conundrum-without-an-answer and the empty sillinesses of Monsieur Matisse.

Yet Sickert was a rare voice defending the works of Van Gogh amongst hostile critics, and his consideration of Gauguin illustrated his awareness of the artist’s work since the mid-1880s.

He was also humorously self-deprecating of his previous critiques. He recalled his first impression of Gauguin: ‘in a street in Dieppe, of a sturdy man with a black moustache and a bowler… no longer a youth, who was thinking of throwing up a good berth in some administration in order to give himself up entirely to the practice of painting. I am ashamed to say that the sketch I saw him doing left no very distinct impression on me and that I expressed the opinion that the step he contemplated was rather imprudent than otherwise’. Essentially, Sickert advised Gauguin not to give up the day job.

His British contemporaries fared little better. In the late 1880s, he embarked on a campaign to modernise the New English Art Club, of which he was a member, by celebrating works that embraced Impressionism and criticised artists who tended to hark back to the rural realism of the 1850s.

Consider his scathing opinion on Frank Bramley’s 'A Hopeless Dawn' (1889), a narrative of a grieving young woman mourning the loss of her betrothed at sea:

I would sentence admirers of Mr Bramley’s transpontine studio realism to no worse form of correction than a condemnation to live three weeks with “Hopeless Dawn”

Confidences, Lawrence Alma-Tadema, 1869 (on display in room 8 at the Walker Art Gallery)

Outside of the NEAC he also gleefully attacked the art establishment. With reference to Royal Academician Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema’s classicism, Sickert stated his works ‘would at best only tell posterity what a cultured and learned gentlemen who lived in St John’s Wood thought the Romans and Egyptians were like.’ Society portraitist John Singer Sargent was all ‘wriggle and chiffon’, whilst:

Roger Fry said it took Degas forty years to get rid of his cleverness: but I think that he himself will take more than forty to get it.

Contemporaries, especially those who distanced themselves from Sickert, could also expect his attention. In early 1914, his Camden Town Group colleagues Harold Gilman and Charles Ginner established their own ‘Neo-Realist’ movement. Inspired by post-impressionist aesthetics, rich in colour and vigorous brushwork, it marked a clear distancing from Sickert’s darker Impressionist influence.

After Sickert’s review of the New English Art Club summer exhibition, in which he criticised the excessive use of impasto, a technique the Neo-Realists enthusiastically practiced, Gilman retaliated by mocking Sickert as ‘The Worst Critic in London’. Sickert volleyed with an article discussing Gilman and Ginner's work, headlining it with the pointed title:

The Thickest Painters in London.

Mrs Mounter, Harold Gilman, 1916 (on display in room 11 at the Walker Art Gallery)

One of Gilman and Ginner’s supporters, the Vorticist Wyndham Lewis, no shrinking violet himself when it came to a loaded word or two, later recalled Gilman’s reaction to Sickert’s late Camden Town works:

Sickert's commerce with these condemned browns was as compromising as intercourse with a proscribed vagrant.

Battle lines were drawn.

At a Chelsea dinner party Lewis would be the target of a particularly impish Sickert put-down. The writer Osbert Sitwell recalled an evening in which Sickert had the spotlight. Lewis, more used to being the centre of attention, was riled by Sickert’s dominance. Towards the end of the evening Sickert presented Lewis with a cigar in a gesture of goodwill:

I give you this cigar because I so greatly admire your writings.

Lewis was in the process of returning the gift with a ‘dazzling smile’ when Sickert mischievously added:

If I liked your paintings, I’d give you a bigger one!

It’s important to note Sickert’s wit was usually unleashed in the service of deflating artistic arrogance. Sickert’s work itself had often been on the receiving end of some rather scathing criticism. His early paintings of London music halls were frequently attacked by art critics; ‘Mr Walter Sickert is a disagreeable failure’, whilst his later ‘English Echoes’ series were regarded as ‘ridiculously feeble’.

Limehouse, James McNeill Whistler, 1859 (in the collection at the Walker Art Gallery, not on display)

Sickert was, however, a generous and supportive critic. Take a look at his thoughts on his early mentor:

… one of the, if not the most original artists now among us is James Abbott McNeill Whistler

Or his opinion of Degas:

The one great French painter, perhaps one of the greatest artists the world has ever seen….

Both Whistler and Degas were his friends, of course, but his enthusiastic support would extend to younger artists such as Spencer Gore, Nina Hamnett and Anna Hope Hudson.

Sickert championed the underdog and relished berating ill-informed fellow critics, his venom reserved for the ‘neo-stinkers.’ Throughout though, Sickert’s criticism was playful, teasing and ultimately in the cause of artistic progress. As he later, with some mock modesty, said:

What puzzles me, … is the cocksureness of writers who cannot even draw as well as I do, which isn’t saying much.