The other Plimsoll - Samuel's 'untiring coadjutor'

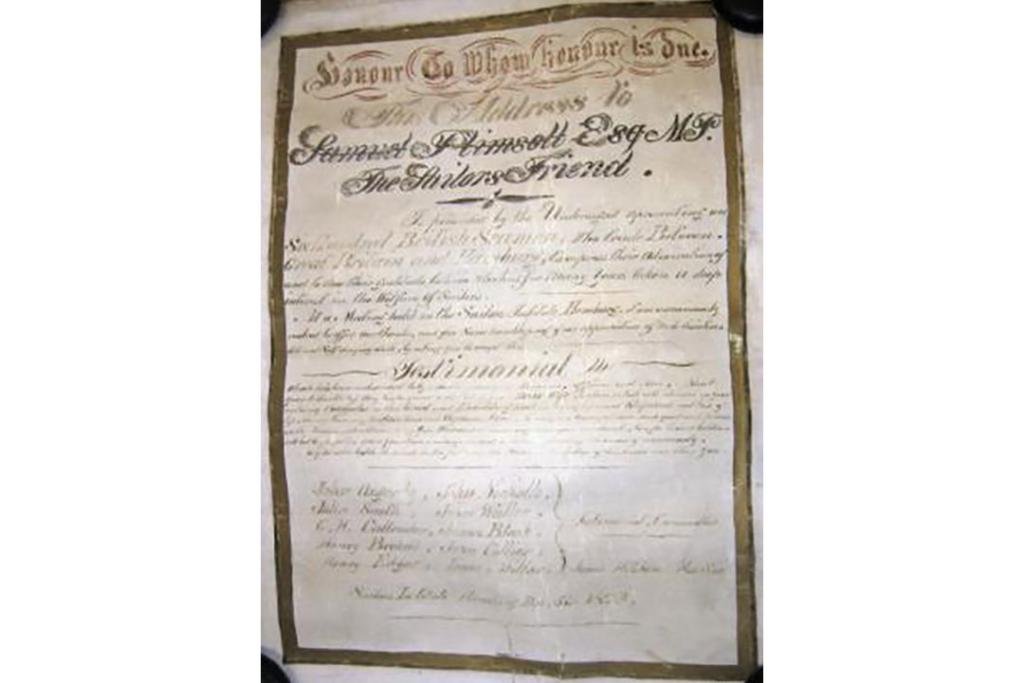

"Honour to whom honour is due..." Testimonial address to Samuel Plimsoll, Maritime Archives collections DX/1110

"I like to think that the Plimsoll line should be regarded as a commemoration not just of Samuel Plimsoll, but of his wife Eliza Plimsoll, whose idea it was originally that he should initiate his campaign for the defence of sailors, and who was definitely dedicated to the cause as he was." – Nicolette Jones lecture, 2008

As a society we are becoming more aware of the vast swathes of people whose stories have been excluded from, or side-lined within, the historical narrative. This includes (but is certainly not limited to) women, people of colour, the disabled and LGBTQ+ people. It can be difficult to combat this when a lack of acknowledgment from their contemporaries has often been compounded by the way history books, and museum collections, have, in previous years, focussed on the privileged and powerful. It is important we remember though that just because these stories have not been told does not mean that there is nothing to tell.

What I particularly like about Eliza Plimsoll’s story is that, though sadly neglected now, she was acknowledged by her contemporaries; indeed it was their words that alerted me to her significance. In researching her husband, Samuel, I came across a beautiful testimonial address in our Maritime Archives collections, awarded to him by the Sailors Institute in Hamburg for services in the interest of sailors’ welfare. When I sat down to read it though it became clear that Samuel was not the only Plimsoll this was intended to thank.

"...your Dear Wife, to whom we look with reverence as your untiring Coadjutor in this Great and Enabling Work in trying to prevent Shipwreck and loss of life, thereby lessening Widows tears and Orphans, Cries." [sic]

The more I researched the Plimsolls the more the use of the word ‘coadjutor’ seemed particularly apt. Samuel and Eliza’s marriage appears to have been a genuine, and very productive, partnership. Even powerful charismatic figures like Samuel Plimsoll do not achieve things on their own through sheer force of will. They are supported, encouraged and tempered by those who work with them.

Eliza was perhaps the perfect foil to Samuel, intelligent, patient and emotionally mature, a worthy complement to his passionate impulsiveness and sentimental nature. She was also tireless in her support of seafarers, just like her husband. Eliza chose not to speak publically, letting Samuel speak for her (he would even quote her verbatim), but worked quietly both behind the scenes and at her husband’s side to further their cause. When he was battling in the House of Commons, literally crying out in defence of seafarers, she was right there in the Ladies’ Gallery watching.

There was nothing passive about her role as an onlooker though. As contemporary London publication Figaro put it in an article after her death in 1882:

"The late Mrs. Plimsoll will long be remembered in the Press Gallery. Thanks to the ex-member for Derby's (Mr. Plimsoll) allusions to 'dear Eliza,' and the influence she exerted on his political action, she was, in fact, more than a name to the British public generally; but the Parliamentary reporters have special reason to bear her in mind."

It then goes on to recount Eliza’s side of the story of Samuel’s infamous loss of temper and breach of parliamentary protocol. Eliza had made her way to the Ladies’ Gallery that day with a bag so large that parliamentary staff had tried to relieve her of it, but Eliza was determined and not to be denied. In it were her husband’s night things as he was expected to be away from home for the night, as she had told the doorkeeper, but also something else it seems.

Samuel and Eliza had suspected trouble was coming with the Merchant Shipping Bill that was scheduled to be debated that day. Their campaign had endured so many delays and setbacks that it seemed inevitable that more would come. They did, Prime Minister Disraeli said that the bill was to be deferred until after the summer recess, triggering Plimsoll’s outburst. It also prompted action from Eliza. The Ladies’ Gallery is located above the Press Gallery in the House of Commons, perfectly situated for Eliza to scatter over the press below her printed copies of her husband’s protest. It would seem from the article in Figaro that it was a move long remembered by the press. It described her actions as “characteristic” of the “staunch North-countrywoman”.

The year following her death, 1883, is the first time we see Samuel break from his campaigning. Though he did in time recover and remarry, Eliza’s loss staggered him so badly at first that even his great passion for seafarers’ rights was stalled. Their marriage had been a love match and a partnership in every sense. Eliza receives much less acknowledgement now for her role than she did in her own lifetime. She chose not to speak publically, but she communicated well enough through her hard work that contemporary seafarers knew her for their champion just as readily as her husband.

Samuel has at least two public memorials in the UK (in Bristol and London), a day named for him (10th February, his birthday), and plaques on the houses he lived in. All I could find for Eliza was a restaurant named after her in a resort in California.

On 8 March each year International Women’s Day is a chance to remember not only Eliza but all the other women whose stories have not received the attention they deserved. It is also a chance to consider whose voices are still not being heard, who is in danger of being side-lined in the historical narrative of our own era?