18th century wig curler found during excavations before the construction of the Crown Court in Liverpool

The

HAIR exhibition in the Museum of Liverpool explores how Black hair styles have evolved and how they reflect wider social change and political movements. It considers the ways in which hairstyles have reflected status, identity and creativity from early African origins to the present. As an archaeologist this got me thinking about what we might be able to interpret about Black British people's hairstyles from archaeological evidence.

In the

regional archaeology collection there are a number of 18th century wig curlers, especially a group excavated at South Castle Street, some of which are on display in the

History Detectives gallery. These were discovered in excavations before the Crown Court was built on Derby Square. These small ceramic objects would have been used on new wigs, or those in need of restyling, to create the even curls which were fashionable in that period. Wig hair would have been rolled in strips of damp paper around heated curlers and then tied with rags and baked in an oven. Wig curlers of different diameters are found, which probably reflects different lengths of hair being curled.

It's fascinating to find these everyday items and imagine the world in which they were used. However, it is often difficult in archaeology to understand the detail of the identity of the people who used the objects we find. Wigs would have been hand-made and expensive, so would only have been worn by the wealthy, but might this have included any 18th century Black Liverpudlians?

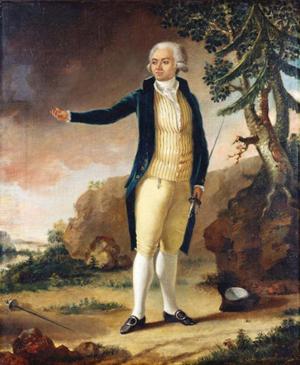

Black French musician, composer and fencer, the Chevalier de Saint Georges wearing a fashionable wig. Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2015

While many Liverpool merchants made their fortune through the

transatlantic slave trade, the majority of Black people trafficked into slavery travelled from Africa to the Americas. The cotton that enslaved Africans grew on plantations in the Americas was exported back to Britain, much into the port of Liverpool. However, there was a small population of Black people living in Liverpool in the 18th century. Historian Ray Costello describes the agreements for African leaders' children to travel to Liverpool for education, estimating that by the 1780s around 50-80 Black children were in school in Liverpool. Many wealthy 18th century households had Black domestic servants. And there were a few Black people who worked their way out of slavery and became part of the more wealthy elite in British towns. For example,

Olaudah Equiano, known as Gustavus Vassa, who published his autobiography in 1789. This best-seller contained

gruelling descriptions of the experience of slavery, and was considered highly influential in gaining passage of the Slave Trade Act in 1807. Living in London, Equiano cut and styled his natural hair to fit-in with contemporary styles, but it's unlikely he used wig curlers and there are no contemporary images of him which suggest he wore a wig.

Across Europe, though, there were fashionable Black people following the latest styles. For example the Chevalier de Saint Georges, a wealthy Black French musician, composer and fencer. He was moving in grand circles, working in prestigious roles in the court of Louis XV and in contact with the British royal family. It's likely this portrait of him by Robineau was painted for George IV. He is shown with a hair style which appears to be a wig, and would have required wig curlers like those found in Liverpool. Saint Georges' biographer, Pierre Bardin, describes that Saint Georges, the son of a White father and a Black mother, would have suffered racism, "his inborn talents were magnified by relentless effort... to overcome the racial barrier which put him in the disdained social class of 'Mulatres'", referring to the contemporary term 'mulatto'. The ways in which Saint Georges dressed and wore his hair or a wig might, therefore, have been a statement of his identity, actively aligning himself with his wealthy contemporaries.

While we have minimal evidence about 18th century Black people living in Liverpool, records indicate that as the overall population of the town grew, so did the Black population. Families from many different backgrounds settled here, and Ray Costello's research has revealed that Black British babies were being born in Liverpool as early as the 1750s. When archaeologists excavate finds from this period it's almost always impossible to know who they belonged to, but the ways in which objects reflect people's lives, activities, and identity is something we do try to consider, drawing on all the available evidence.

18th century wig curler found during excavations before the construction of the Crown Court in Liverpool

The HAIR exhibition in the Museum of Liverpool explores how Black hair styles have evolved and how they reflect wider social change and political movements. It considers the ways in which hairstyles have reflected status, identity and creativity from early African origins to the present. As an archaeologist this got me thinking about what we might be able to interpret about Black British people's hairstyles from archaeological evidence.

In the regional archaeology collection there are a number of 18th century wig curlers, especially a group excavated at South Castle Street, some of which are on display in the History Detectives gallery. These were discovered in excavations before the Crown Court was built on Derby Square. These small ceramic objects would have been used on new wigs, or those in need of restyling, to create the even curls which were fashionable in that period. Wig hair would have been rolled in strips of damp paper around heated curlers and then tied with rags and baked in an oven. Wig curlers of different diameters are found, which probably reflects different lengths of hair being curled.

It's fascinating to find these everyday items and imagine the world in which they were used. However, it is often difficult in archaeology to understand the detail of the identity of the people who used the objects we find. Wigs would have been hand-made and expensive, so would only have been worn by the wealthy, but might this have included any 18th century Black Liverpudlians?

18th century wig curler found during excavations before the construction of the Crown Court in Liverpool

The HAIR exhibition in the Museum of Liverpool explores how Black hair styles have evolved and how they reflect wider social change and political movements. It considers the ways in which hairstyles have reflected status, identity and creativity from early African origins to the present. As an archaeologist this got me thinking about what we might be able to interpret about Black British people's hairstyles from archaeological evidence.

In the regional archaeology collection there are a number of 18th century wig curlers, especially a group excavated at South Castle Street, some of which are on display in the History Detectives gallery. These were discovered in excavations before the Crown Court was built on Derby Square. These small ceramic objects would have been used on new wigs, or those in need of restyling, to create the even curls which were fashionable in that period. Wig hair would have been rolled in strips of damp paper around heated curlers and then tied with rags and baked in an oven. Wig curlers of different diameters are found, which probably reflects different lengths of hair being curled.

It's fascinating to find these everyday items and imagine the world in which they were used. However, it is often difficult in archaeology to understand the detail of the identity of the people who used the objects we find. Wigs would have been hand-made and expensive, so would only have been worn by the wealthy, but might this have included any 18th century Black Liverpudlians?

Black French musician, composer and fencer, the Chevalier de Saint Georges wearing a fashionable wig. Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2015

While many Liverpool merchants made their fortune through the transatlantic slave trade, the majority of Black people trafficked into slavery travelled from Africa to the Americas. The cotton that enslaved Africans grew on plantations in the Americas was exported back to Britain, much into the port of Liverpool. However, there was a small population of Black people living in Liverpool in the 18th century. Historian Ray Costello describes the agreements for African leaders' children to travel to Liverpool for education, estimating that by the 1780s around 50-80 Black children were in school in Liverpool. Many wealthy 18th century households had Black domestic servants. And there were a few Black people who worked their way out of slavery and became part of the more wealthy elite in British towns. For example, Olaudah Equiano, known as Gustavus Vassa, who published his autobiography in 1789. This best-seller contained gruelling descriptions of the experience of slavery, and was considered highly influential in gaining passage of the Slave Trade Act in 1807. Living in London, Equiano cut and styled his natural hair to fit-in with contemporary styles, but it's unlikely he used wig curlers and there are no contemporary images of him which suggest he wore a wig.

Across Europe, though, there were fashionable Black people following the latest styles. For example the Chevalier de Saint Georges, a wealthy Black French musician, composer and fencer. He was moving in grand circles, working in prestigious roles in the court of Louis XV and in contact with the British royal family. It's likely this portrait of him by Robineau was painted for George IV. He is shown with a hair style which appears to be a wig, and would have required wig curlers like those found in Liverpool. Saint Georges' biographer, Pierre Bardin, describes that Saint Georges, the son of a White father and a Black mother, would have suffered racism, "his inborn talents were magnified by relentless effort... to overcome the racial barrier which put him in the disdained social class of 'Mulatres'", referring to the contemporary term 'mulatto'. The ways in which Saint Georges dressed and wore his hair or a wig might, therefore, have been a statement of his identity, actively aligning himself with his wealthy contemporaries.

While we have minimal evidence about 18th century Black people living in Liverpool, records indicate that as the overall population of the town grew, so did the Black population. Families from many different backgrounds settled here, and Ray Costello's research has revealed that Black British babies were being born in Liverpool as early as the 1750s. When archaeologists excavate finds from this period it's almost always impossible to know who they belonged to, but the ways in which objects reflect people's lives, activities, and identity is something we do try to consider, drawing on all the available evidence.

Black French musician, composer and fencer, the Chevalier de Saint Georges wearing a fashionable wig. Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2015

While many Liverpool merchants made their fortune through the transatlantic slave trade, the majority of Black people trafficked into slavery travelled from Africa to the Americas. The cotton that enslaved Africans grew on plantations in the Americas was exported back to Britain, much into the port of Liverpool. However, there was a small population of Black people living in Liverpool in the 18th century. Historian Ray Costello describes the agreements for African leaders' children to travel to Liverpool for education, estimating that by the 1780s around 50-80 Black children were in school in Liverpool. Many wealthy 18th century households had Black domestic servants. And there were a few Black people who worked their way out of slavery and became part of the more wealthy elite in British towns. For example, Olaudah Equiano, known as Gustavus Vassa, who published his autobiography in 1789. This best-seller contained gruelling descriptions of the experience of slavery, and was considered highly influential in gaining passage of the Slave Trade Act in 1807. Living in London, Equiano cut and styled his natural hair to fit-in with contemporary styles, but it's unlikely he used wig curlers and there are no contemporary images of him which suggest he wore a wig.

Across Europe, though, there were fashionable Black people following the latest styles. For example the Chevalier de Saint Georges, a wealthy Black French musician, composer and fencer. He was moving in grand circles, working in prestigious roles in the court of Louis XV and in contact with the British royal family. It's likely this portrait of him by Robineau was painted for George IV. He is shown with a hair style which appears to be a wig, and would have required wig curlers like those found in Liverpool. Saint Georges' biographer, Pierre Bardin, describes that Saint Georges, the son of a White father and a Black mother, would have suffered racism, "his inborn talents were magnified by relentless effort... to overcome the racial barrier which put him in the disdained social class of 'Mulatres'", referring to the contemporary term 'mulatto'. The ways in which Saint Georges dressed and wore his hair or a wig might, therefore, have been a statement of his identity, actively aligning himself with his wealthy contemporaries.

While we have minimal evidence about 18th century Black people living in Liverpool, records indicate that as the overall population of the town grew, so did the Black population. Families from many different backgrounds settled here, and Ray Costello's research has revealed that Black British babies were being born in Liverpool as early as the 1750s. When archaeologists excavate finds from this period it's almost always impossible to know who they belonged to, but the ways in which objects reflect people's lives, activities, and identity is something we do try to consider, drawing on all the available evidence.