The Sickert Effect

Walter Sickert’s influence on artists has spanned decades, from the 1920s to the 2020s. Professor Liz Rideal of London’s Slade School of Art looks at Walter Sickert’s influence on contemporary artists and how his style and techniques are still being used.

Walter Sickert invented ways to paint his particular way of seeing, and portrayed humanity, both ordinary and privileged. He also painted numerous outdoor scenes, incorporating the mundane and monumental buildings of Venice, Dieppe and Bath, revelleling in a sense of space and place. Famously, he painted from newspaper photography, using press images to feed both his eyes and his imagination. This modern technique helps to envelop us in his interpretation of the world across different genres. Sickert’s progressive ideas in painting make him as relevant today as he was in his own time. Here are some examples of artists and artworks that take a similar approach, connecting with his ongoing artistic legacy.

John Bratby, Three People at a Table, 1955

Ennui, 1917-18, Walter Sickert, Photo courtesy of © Ashmolean Museum

John Bratby, Three People at a Table, 1955

This ‘Kitchen Sink’ painter owes much to Sickert in his formulations of the everyday. Bratby’s Three People at a Table (1955) chimes in perfectly as an updating of the strained intimacy apparent in Ennui, with his protagonists locked around a table in similar state of bored silence.

Bratby’s art dealer was Helen Lessore, Sickert’s sister-in-law. Lessore represented artists including Bacon, Auerbach and Kossoff, all of whom are repeatedly linked to Sickert and his aura. Lucian Freud iterates the same disconnected ennui as he portrays himself with his second wife in Paris, in Hotel Bedroom, 1954, and confirming his distinctive early ‘brand’ of alienated realism.

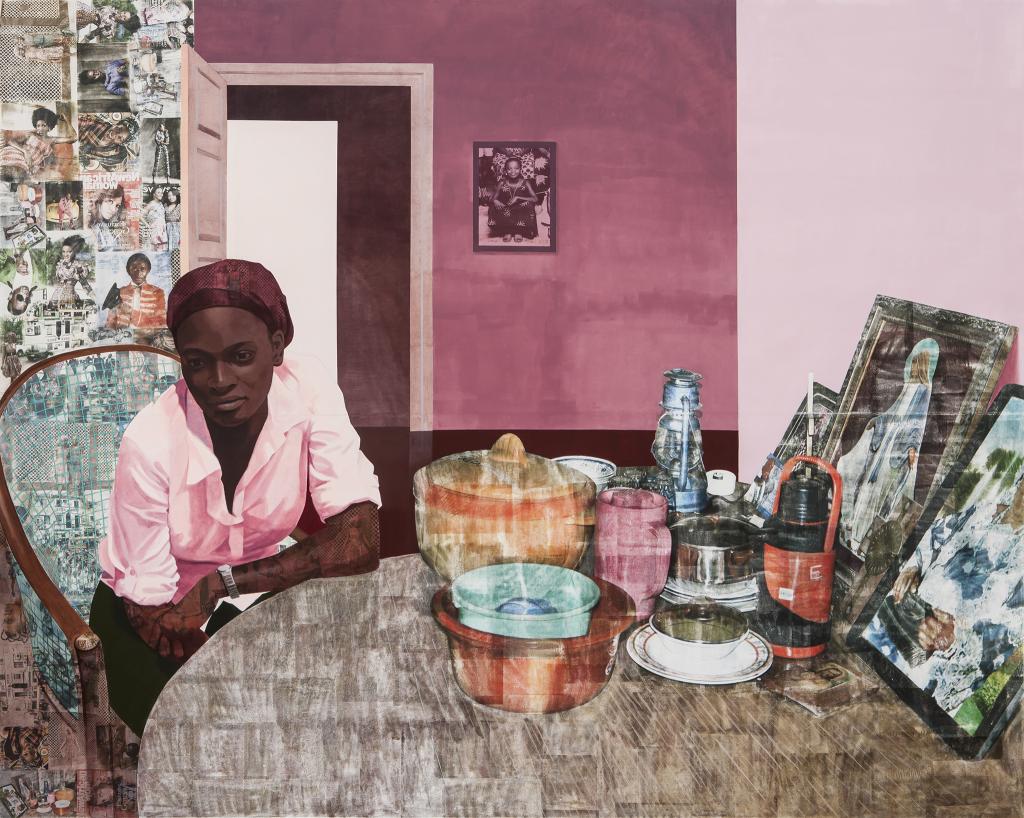

Njideka Akunyili Crosby, Mama, Mummy and Mamma, 2015

Njideka Akunyili Crosby, Mama, Mummy Mamma, 2015

Crosby’s artwork updates techniques that Sickert used with reproduced newspaper photographs. In this artwork, one wall is covered in magazines and prints. On the other, a dull rosy tone evokes the stifling atmosphere of a 19th-century interior. Crosby mixes photos of her family with photos of celebrities and the two create, like Sickert, a cocktail of reproduction and repetition.

With the progress of new technologies, the modern world has become compressed and agitated all at once. Artists like Crosby constantly embrace the potential of new media, using secondary photographic material in their work.

Elaine de Kooning, J. F. Kennedy, 1962

In 1962, Elaine de Kooning was commissioned to paint J. F. Kennedy, and there is a clear synergy between this rendering and Sickert’s painting H.M.King Edward VII (1936).

The fate of the King and the President made them subsequently notorious - a further layering of time for the viewer. The portraits were inspired by photography but show them caught in subservience to their large, but tight, rectangular compositions. At that time photography and television were largely black and white, relatively small, and certainly not the size of these innovative portraits.

The remains of Sickert’s scaling-up of an image can be seen in his portrait, Miss Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies as Isabella of France, 1932, a monumental work measuring 245.1 x 92.1cm. It was derived from a small publicity photograph taken of the actress on stage by Bertram Park.

Agalis Manessi, Looking at Minnie Cunningham, 2019

Minnie Cunningham at the Old Bedford, 1892, Walter Sickert, © Tate

Agalis Manessi, Looking at Minnie Cunningham, 2019

Agalis Manessi reveals that it was the “intense red on Minnie Cunningham’s dress (that) made me look at her again and again”. Sickert’s Minnie Cunningham at the Old Bedford, 1892, is a tiny waif compared to La Louvre, and painted from drawings made in situ. Small in scale, the red of her dress sings out along with the sitter. When first exhibited it bore the subtitle from one of her songs; ‘I’m an old hand at love, though I’m young in years’.

Red is the dominant colour in another stage painting, The P.S. Wings in an O.P. Mirror, c.1889 (Musée des Beaux-Arts, Rouen). This complex image containing reflections also exploits the audience in the immediate foreground, enveloping us in the action. The same strategy is used by Jack B. Yeats in his work The Liffey Swim of 1923, over thirty years later.

La Hollandaise, 2009, Jock McFadyen

La Hollandaise, 1906, Walter Sickert, © Tate

Jock McFadyen, La Hollandaise, 2009

Jock McFadyen appears to be the most blatantly influenced by Sickert, having made a direct copy of La Hollandaise in 2009. McFadyen was attracted to the real-life scenarios Sickert painted, especially his nudes. Sickert often presented women without ‘traditional’ Victorian frills and the poses are locked within the dingy, rigid frames of the iron bedsteads.

This snapshot of examples goes to show that the ‘Sickert effect’ trickles forward through time and is alive and well within contemporary art.

Contemporary points of view:

Jock McFadyen comments about the artist:

I think Sickert was acutely aware of the challenges the 20th century presented for realist painting. Photography, radio and movies as well as aeroplanes and motor cars were invented during his lifetime. This influenced his painting in my view and the obsession with news stories (Crippen, Jack the Ripper etc.) and the use of news photography are a slightly desperate attempt to keep his painting abreast of the rapidly encroaching age of media which was beginning to elbow painting aside as a describer of the world. A lost cause as TV and documentary would eventually reposition realism to the realm of style and fashion after the artist's death.

Statement by the artist in personal correspondence, 23/6/21

Lucian Freud is often cited as the artist who follows in Sickert’s footsteps and his disciple, artist Celia Paul, comments about these nudes:

I think there’s a compassion in the way he portrays women, an intimacy…there’s a real sense of his charm. These women are delighted to be sitting for him. You get the feeling that they actually loved being looked at by him. They’re erotic feelings in the best sense of the word. Even though there’s a kind of intimate drama in all of the interiors, there is a quite lonely feeling. I sort of imagine him looking in through the window at something he hasn’t got and he’s decided that a domestic life is probably maybe too complicated for him. (Walter Sickert and the Theatre of British Art at War 2/4 (Episode 2) 10:00).

Alex Massouras, an artist known for narrative etchings that reveal mysterious stories, writes:

I doubly like Sickert for his paintings and persona: the writing is quite generous and witty, often amazingly concise too. The aphorisms are as good as any Wilde came up with: 'There is no such thing as modern art. There is no such thing as ancient art' etc. The paintings rehearse the tension between painting and photography which played out for the rest of the century (and into this one). His treatment of imagery feels quite 'pop', but he also offers a template for a lot of painting today. I'm thinking especially of the compressed palette of Luc Tuymans or Kaye Donachie. So I like him as a fundamentally anachronistic painter, both very old modern (in links to nineteenth century European painting) and contemporary in his immersion in the currency of images.

Statement by the artist in personal correspondence, 15/6/21

Artist Agalis Manessi added her version of Minnie Cunningham to her series of ceramic plate portraits:

I am drawn to Sickert’s use of colours, there is always a sense of mystery in his brushstrokes and colour choices. That intense red on Minnie Cunningham’s dress made me look at her again and again, and I wanted to have a go at depicting her on one of my portrait plates.

Statement from the artist in personal correspondence, 23/6/21

Keith Coventry focuses on Sickert’s The Echoes:

Sickert was accused of being nostalgic when he painted ‘The Echoes’, but in a way the irony is that out of that maybe nostalgic looking back at the past he created what I think are some of the most modern pictures. By squaring up, by faithfully reproducing what is in every square, it makes the paint more abstract because he’s only looking at it one square at a time. And so because of that you get an incredible two-dimensionality. I just think that that risk-taking element and the idea of appropriation (which is something we seem to think is a very modern thing) …back in 1930s, it must have been quite shocking