‘Troublesome ladies’ and #Vote100

Today marks 100 years since the Representation of the People Act was passed in 1918. This law allowed some women to vote for the first time, but it only applied to women over the age of 30 who had property rights or a university education. The Act also enabled all men over the age of 21 to vote for the first time too.

The campaign for women’s suffrage, or the right to vote, began to gain momentum in the mid 19th century. The Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) was founded in 1903 by former members of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) frustrated by the campaign’s slow progress. Led by Christine Pankhurst, the WSPU sought to attract attention to their cause in new ways. Their motto was ‘Deeds, not words’ and their actions became increasingly disruptive and violent in the years that followed. They committed acts of arson, damaged public buildings and even planted bombs, while others targeted famous works of art in public galleries and museums.

At least fourteen paintings were attacked between 1913 and 1914, with incidents reported at Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, Manchester Art Gallery and the National Portrait Gallery in London amongst others. The most famous occurrence took place on 10 March 1914 when Mary Richardson attacked Velazquez’s painting The Rokeby Venus at the National Gallery in London with a meat cleaver.

We didn’t think the Walker and its collections had been affected by the actions of the suffragettes, but we were inspired by this year’s anniversary to take a closer look at our archives to see if we could find out more.

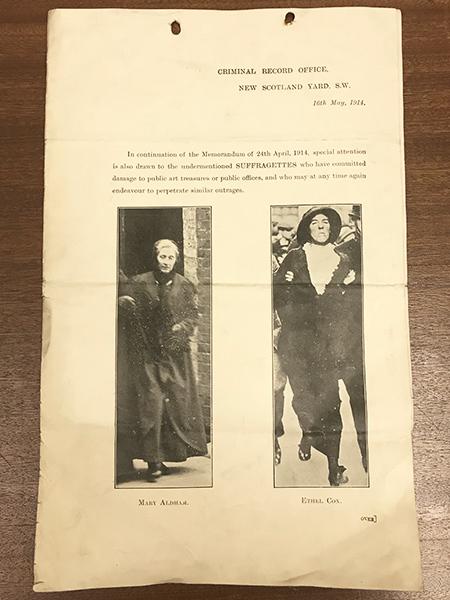

Browsing the records for 1913, the first suffragette attacks on artworks don’t appear to impact the Walker Gallery. This changed the following year as the suffragette campaign persisted and the authorities took the risk to public art collections more seriously. New Scotland Yard circulated photographs and descriptions of the women involved in previous attacks to police forces across the country, warning they ‘may at any time again endeavour to perpetrate similar outrages’.

A letter written by a Walker curator to the police explaining that the gallery has been closed because of the possible threat of attacks on artworks

Central Liverpool Police warned the Walker of the risk posed by the suffragettes in May 1914. It is not clear if the police were reacting to a specific threat but their warning prompted the closure of the Gallery for two days. The Walker’s assistant curator thanked the police in a letter dated 22 May 1914, explaining: ‘we are grateful for your information respecting possible trouble by certain ladies, local or otherwise, and acting on the same we closed the gallery down yesterday afternoon, and have arranged to keep them closed today, your warning leading us to dread trouble on these two days. The committee prefers that the Gallery should be open tomorrow, and if you can place on duty here a plain clothes police officer who has knowledge of the troublesome ladies, my chairman Alderman Lea will be much obliged.’

A letter written by a Walker curator to the police explaining that the gallery has been closed because of the possible threat of attacks on artworks

Central Liverpool Police warned the Walker of the risk posed by the suffragettes in May 1914. It is not clear if the police were reacting to a specific threat but their warning prompted the closure of the Gallery for two days. The Walker’s assistant curator thanked the police in a letter dated 22 May 1914, explaining: ‘we are grateful for your information respecting possible trouble by certain ladies, local or otherwise, and acting on the same we closed the gallery down yesterday afternoon, and have arranged to keep them closed today, your warning leading us to dread trouble on these two days. The committee prefers that the Gallery should be open tomorrow, and if you can place on duty here a plain clothes police officer who has knowledge of the troublesome ladies, my chairman Alderman Lea will be much obliged.’

Photos of alleged disruptive Suffragettes Walker staff were told to look out for

Earlier that month, as reported in the Liverpool Daily Post on 8 May 1914, visitors had been banned from bringing bags, cameras and packages in to the Walker and four additional commissionaires, or guards, had been employed to patrol the galleries in the hope of averting a suffragette attack. Undisclosed ‘special precautions’ had also been put in place to protect the gallery’s most popular and valuable paintings including works by Millais, Rossetti and Holman Hunt.

Although no attack took place, further measures were again put in place in June 1914, including the introduction of bag searches for all women entering the gallery. Plain clothes police officers were also installed at the Walker for at least five days that month in response to a police warning. This heightened security was probably caused by the attack on a George Romney painting at Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery by Bertha Ryland, a member of the WSPU, on 10 June.

The attacks on paintings stopped when the First World War broke out, along with the rest of the suffragettes’ actions, as they put aside their campaign temporarily to support the war effort. We don’t know today if the threat to the Walker’s collection was real but the staff at the time certainly perceived it to be. The individual actions of the suffragettes attracted more attention to their cause but it was the day-to-day changes like those implemented at the Walker which ensured the issue remained ever present in people’s minds.

We will be looking more closely at the archives to see what else we can discover about this aspect of the Walker’s history in the coming months, we’ll publish any new information we discover here.

Photos of alleged disruptive Suffragettes Walker staff were told to look out for

Earlier that month, as reported in the Liverpool Daily Post on 8 May 1914, visitors had been banned from bringing bags, cameras and packages in to the Walker and four additional commissionaires, or guards, had been employed to patrol the galleries in the hope of averting a suffragette attack. Undisclosed ‘special precautions’ had also been put in place to protect the gallery’s most popular and valuable paintings including works by Millais, Rossetti and Holman Hunt.

Although no attack took place, further measures were again put in place in June 1914, including the introduction of bag searches for all women entering the gallery. Plain clothes police officers were also installed at the Walker for at least five days that month in response to a police warning. This heightened security was probably caused by the attack on a George Romney painting at Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery by Bertha Ryland, a member of the WSPU, on 10 June.

The attacks on paintings stopped when the First World War broke out, along with the rest of the suffragettes’ actions, as they put aside their campaign temporarily to support the war effort. We don’t know today if the threat to the Walker’s collection was real but the staff at the time certainly perceived it to be. The individual actions of the suffragettes attracted more attention to their cause but it was the day-to-day changes like those implemented at the Walker which ensured the issue remained ever present in people’s minds.

We will be looking more closely at the archives to see what else we can discover about this aspect of the Walker’s history in the coming months, we’ll publish any new information we discover here.