What happened to Black Germans during the Holocaust?

Professor Eve Rosenhaft reveals some of the personal histories of Black Germans during the Holocaust. Find out how their resilience under the Nazi regime enabled them to rebuild their lives after the war.

When Hitler came to power in January 1933, there were probably about 2000 people of African descent in Germany. They included African-American, Afro-Caribbean and African people passing through, working or recently settled. But the core of Germany’s Black community was made up of men from Germany’s former colonies – East Africa, Togo and Cameroon – with their German-born wives and ‘mixed -race’ children.

‘Mixed’ families represented a particular challenge to the Nazis’ vision of a racially pure Germany. Officially defined as being ‘of alien blood’, people of African descent were subject to exclusion, harassment, internment (sometimes leading to death), and compulsory sterilisation. The origins of these racist Nazi policies and their white supremacy movement, are of course firmly rooted in the legacy of transatlantic slavery.

Tracing the histories of these ordinary people in extraordinary times involves research in archives all over the world. Over the past twenty years, their personal stories have been pieced together from memoirs, interviews and official documents, and research continues to reveal new details.

One story is that of Zoya K.

Daughter of a Cameroonian man and his German wife, Zoya was raised by her mother after her parents divorced and was 15 when Hitler came to power in 1933.

Life under the Nazi regime

In the summer of 1933, Nazis took over the suburban villa where Zoya and her mother lived, declaring that they deserved no more than a cellar. In 1936 she was expelled from her secondary school on racial grounds and declared stateless. Having hoped to study medicine, she was now unable to get work of any kind, so she trained as a dancer and travelled to France with a theatrical revue. Back in Germany in 1939, she had to prove that she was an Aryan in order to continue working. A check of her family background revealed that her mother's father had been a baptised Jew, and the result was that both she and her mother now fell under Nazi antisemitic legislation. Zoya was banned from the stage, her mother subject to forced labour in industry once the war broke out.

In early 1941, pregnant with the child of her white partner, Zoya was summoned to a meeting with the Gestapo at which she was threatened with sterilisation. She decided to go underground. With the help of her mother and her partner she lived in hiding around Berlin until December 1943, when she fled to Prague with her son. Arrested there by the Gestapo in November 1944, she was held in prison with her young son until the liberation. In prison Zoya was beaten and contracted tuberculosis, but she survived.

Zoya’s life is typical of the experiences of Black people in Nazi Germany: harassment and social exclusion beginning as soon as the Nazis took power, the denial of opportunities for schooling and work, the increasing pressure of police surveillance and gradual closure of safe spaces and opportunities for escape in wartime. It is also typical that the threat of sterilisation stands at the centre of Zoya's experience. Sterilisation was the main weapon of Nazi policy, since ‘mixed’ couples and their children were living proof that people of different races could live together.

Rebuilding communities

Zoya’s family belonged to a Black community that was beginning to crystallise in Germany by the 1930s, forming social networks and organising to defend itself. The Nazis attacked those networks by banning anticolonial and anti-racist organisations, forcing people to emigrate or go underground, breaking lives and careers, and trying to prevent the birth of new generations. After the war, networks and families had to be reconstructed, while people’s lives continued to be burdened by the losses and hurts of the Nazi years.

Nevertheless, people did start to rebuild their lives together. A few years after the war Zoya and her friend Dorothea R. started the Pinguin Bar. Dorothea also had a Cameroonian father and a German mother and like Zoya she had been thrown out of her family home by the Nazis and forced to leave school. She had gone into hiding when she was threatened with being sterilised. Also involved in the project was Dorothea’s cousin Josepha V.; with her white husband Josepha had been interned in a concentration camp, while her white mother had been held in prison.

The Pinguin Bar opened in the Berlin West End in 1949. It was not only a sociable space where members of Germany's Black community reconvened, but it also provided opportunities to earn. Black people who were oppressed by the Nazis had a right to compensation. Their claims were processed slowly and reluctantly though, and Zoya was living in poverty in these years. The Pinguin musicians included members of most of the Cameroonian families in Berlin. Many of those who had not already been performers of some kind before the war had had to survive by performing, often in shows and films that promoted colonialism. In the Pinguin they could choose for themselves what they played, and although the décor was African they often played samba, jazz or African-American spirituals.

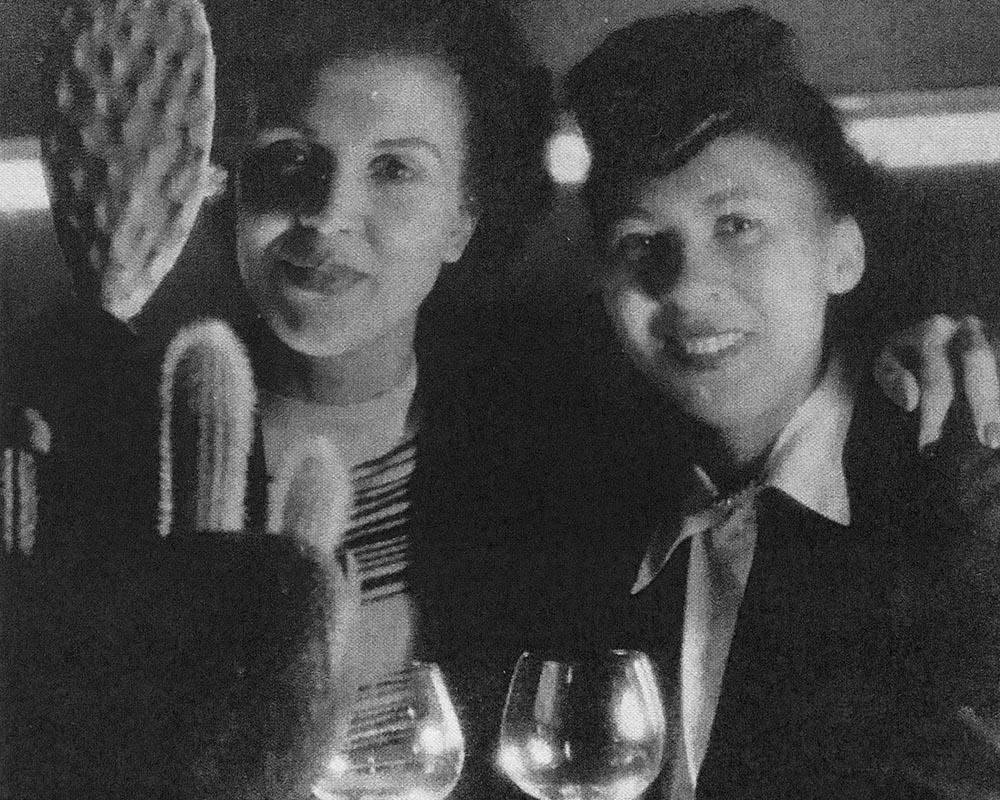

The picture above, of Zoya and Dorothea together in about 1950, shows two women who are still young – perhaps still able to look forward, who are starting to put their lives back together.

Telling their histories

The Pinguin Bar was a success, but it lost its financial backing and closed in 1950, and the first Black German community was largely forgotten. Its surviving members got on with their lives while white German society either forgot or mythologised the colonial era that had brought their fathers to Germany. Public attention shifted to a new generation of Afro-Germans, the children fathered by American GIs in the immediate post-war years (known as 'Besatzungskinder' – ‘occupation babies’), who in their turn suffered the hurts of racism in the new West Germany.

It was only in the 1980s that the young women of that post-war generation, along with the daughters of more recent African immigrants, set out to rediscover their own history. Working alongside the new anti-racist Initiative Schwarzer Menschen in Deutschland (Initiative of Black People in Germany), they found and interviewed survivors of Nazi persecution (including Dorothea R.) and published their stories in a pioneering book in 1986.

Survival, resilience and resistance

Nazi policy towards people of African descent was genocidal; its intention was that Black Germans should cease to exist. While there was no mass roundup of Black people and no systematic killing, the trajectory was towards physical elimination.

The story of Zoya K reminds us how genocide can arrive by gradual steps, the first of which is the creation of political conditions in which everyday harassment and bullying are licensed and racists are empowered.

It also shows how solidarity can contribute to survival, resilience and resistance, and recalls how natural and powerful relations of love and comradeship between Black and white people have been in building and rebuilding communities.

It’s important for us to continue to learn our histories and share our stories, to connect with what has happened in the past and reflect on the conditions for communities today.