Who was Olaudah Equiano?

Writer and abolitionist, his extraordinary memoir brought attention to enslaved people's lives and went on to change history.

Olaudah Equiano was born in 1745 in Essaka, Benin, today's Southeastern Nigeria. By the 18th century the Atlantic Slave Trade was at its height with millions being kidnapped from the West Coast of Africa. In an extraordinary memoir, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano or Gustavas Vassa, the African, Olaudah describes not only his ancestral customs, but his experiences of enslavement from kidnapping to the eventual purchase of his own freedom. While the genre of “slave narratives” have offered thousands of autobiographical accounts of slavery, Olaudah’s life, legacy and the detail in which he describes his experience significantly drove the abolitionist movement.

In his book, Olaudah speaks of Essaka fondly, detailing its customs, hierarchies, resources and belief systems. Hyper aware of the dehumanisation of African culture in the European imagination, he offers a picture removed from 'the primitive', challenging the grounds on which slavery is founded.

When questioning the perceptions Europeans have of Africans he asks:

“Are they treated as men? Does not slavery itself depress the mind, and extinguish all its fire and noble sentiment?”

Determined to 'melt the pride of superiority' based on skin color, he compared an African’s complexion to the darkening of a Spaniards skin and African culture to traditional Jewish customs. He felt that through likeness and comparison he might create a relatability to shift racist views.

At the age of 11, Equiano’s village was attacked. Kidnappings were incredibly common and he alerted his village from a tree when spotting the intruders. Yet, while the village was distracted both himself and his sister were kidnapped. For months Olaudah was sold and traded from family to family and village to village. One night he was reunited with his sister and they held hands as they wept from either side of the man who purchased them. Olaudah would never see his sister or family again. In these recollections Olaudah does not only speak for himself but for the millions of people separated generationally from their families. Through sharing his love for his sister, he hoped recognition of the decimation of black family structures would be acknowledged.

When speaking of his last reunion with his sister:

“Yes thou dear partner of my childish sports! Though sharer of my joys and sorrows! Happy should I ever esteemed myself to encounter every misery for you, and procure your freedom by the sacrifice of my own.” (p.24)

Detailed descriptions of surviving the Middle Passage are rare. After being brought aboard a slave ship Olaudah speaks of his first time encountering Europeans, his fears of being cannibalised and the sickening stench in the belly of the ship. He then arrived in Virginia via Barbados and was sold three times, spending the majority of his life in servitude aboard ships. During this time he served in the 7 years war against France with The Royal Navy and aboard a trade ship in Montserrat in the West Indies.

In the mid 1760’s, Olaudah nearly lost his life. While talking with a group of black men on the property of Doctor Perkins, he was attacked. Perkins was enraged that someone he wasn’t familiar with was on his property. He was eventually found in a jail by his captain and in spite of the doctors expectations of death, he managed to recover. His captain attempted to press charges against Doctor Perkins to no avail.

In 1766 Olaudah purchased his freedom by saving the money he gained from selling petty goods. He offered Mr. King, the man who owned him, £40.00 for his freedom. At first reluctant, Olaudah’s captain convinced King to accept the offer. This moment of serenity, this moment of freedom was captured:

“In an instant all my trepidation was turned into unutterable bliss; and I most reverently bowed myself with gratitude, unable to express my feelings, but by the overflowing of my eyes, while my true and worthy friend, the Captain, congratulated us both with a peculiar degree of heartfelt pleasure.”

After purchasing his freedom, Olaudah faced death once again when his ship was wrecked in the Bahamas. Fleeing on a small boat with his captain they encountered several storms. Finally after arriving in Georgia he was nearly kidnapped before sailing for Martinico. Olaudah went on to encounter the slave uprisings in Monsterrat, join expeditions in the arctic and ultimately devotes his live to the abolition of slavery. Yet his political positionality is not without question when in 1775 he assisted in establishing a plantation in Central America with an intent to Christianise the indigenous population.

In 1787 Olaudah Equiano co- founded Sons of Africa, which is now considered the first black political organisation in Britain. This group was comprised of formerly enslaved individuals that campaigned for the abolition of chattel slavery. The group affected the outcome of the infamous Zong Massacre trial by bringing it to the attention of abolitionist Granville Sharp. By 1788 an anti slave trade petition is presented to Queen Charlotte by Olaudah and the next year he published his autobiography.

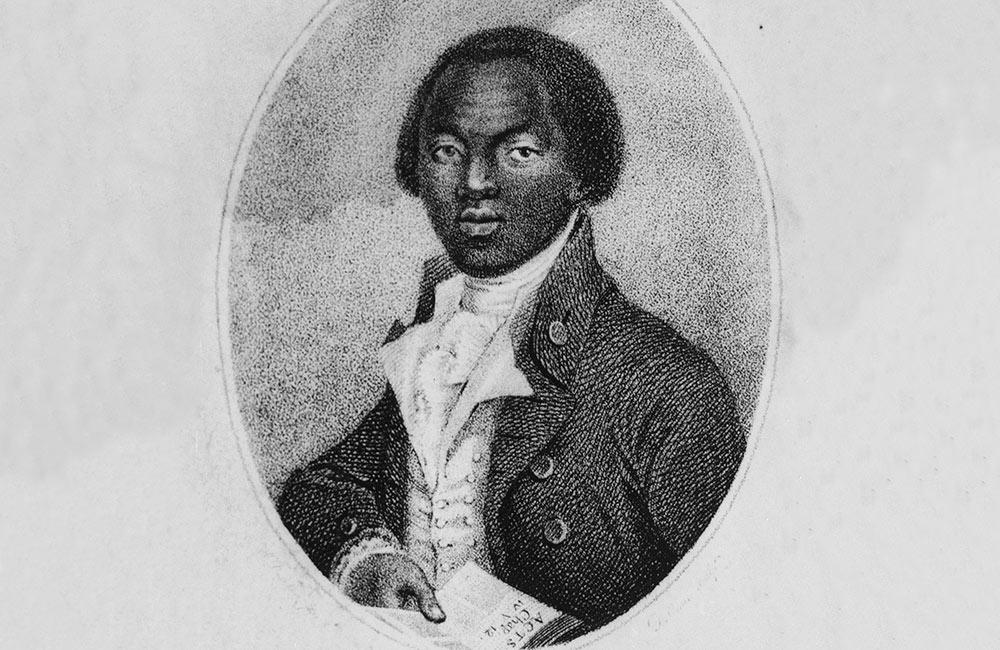

When thinking of the great storyteller and abolitionist Oluadah Equiano one image usually comes to mind, “Portrait of An African”. This 18th century painting is found on the cover of books, museum exhibitions and endless amounts of articles. Yet who is the man in the portrait? After extensive review, it is thought that the portrait is likely not Olaudah. Many have ruled out the possibility of him being a sitter due to the date in which it was painted. Oluadah would not have yet been a free man who would be able to have a portrait made in this style. Some believe it to be a portrait of actor and composer Ignatius Sancho. The portrait arriving at the Royal Albert Memorial Museum in 1943 was a part of a recent exhibition, In Plain Sight: Transatlantic slavery and Devon. In an attempt to create more conversation of Devn’s connection to slavery further discussion has been facilitated on the portraits origin. Gratefully, whoever the sitter truly may be, Olaudah Equiano left us with an incredible self portrait through a detailed personal narrative that would go on to change history.

View Bronze portrait sculpture by Christy Symington here.